Abstract

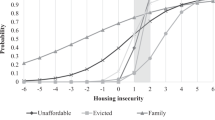

Housing costs are a substantial component of US household expenditures. Those who allocate a large proportion of their income to housing often have to make difficult financial decisions with significant short-term and long-term implications for adults and children. This study employs cross-sectional data from the first wave of the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey collected between 2000 and 2002 to examine the most common US standard of housing affordability, the likelihood of spending 30 % or more of income on shelter costs. Multivariate analyses of a low-income sample of US-born Latinos, whites, African Americans, authorized Latino immigrants, and unauthorized Latino immigrants focus on baseline and persistent differences in the likelihood of being cost burdened by race, nativity, and legal status. Nearly half or more of each group of low-income respondents experience housing affordability problems. The results suggest that immigrants’ legal status is the primary source of disparities among those examined, with the multivariate analyses revealing large and persistent disparities for unauthorized Latino immigrants relative to most other groups. Moreover, the higher odds of housing cost burden observed for unauthorized immigrants compared with their authorized immigrant counterparts remains substantial, accounting for traditional indicators of immigrant assimilation. These results are consistent with emerging scholarship regarding the role of legal status in shaping immigrant outcomes in the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this study, Latinos are an ethnic group that can be of any race; whites and blacks/African Americans refer to those who are not Hispanic. Differences between these three groups are referred to as race/racial differences.

This definition of unauthorized immigrants follows the “unauthorized residents” terminology used by the US Department of Homeland Security (Hoefer et al. 2010).

See Donato and Armenta (2011) for a recent literature review of unauthorized migration.

This study treats immigrants’ legal status as a characteristic of individuals, but recognizes that legality/illegality and authorized/unauthorized are complicated, transitory, and socially constructed concepts based on immigration policy and actions of the US state (e.g., De Genova 2004; Menjívar 2011).

Although this study focuses on nativity and legal status differences among Latinos, other sources of intra-Latino heterogeneity include country of origin/descent, skin tone, social class, and location in the United States (e.g., Espino and Franz 2002; Rodríguez et al. 2008; Telles and Ortiz 2008; Frank et al. 2010).

In households with children under the age of 18, the mother of a randomly selected child was designated the primary caregiver (PCG) and completed a parent questionnaire. In most households, the PCG and the RSA were the same person (RSA/PCG) or in the same nuclear family. In other households, more than one nuclear family resided in the home, and the RSA and the PCG could be from different nuclear families and both families could have filled out the household survey depending on respondent selection criteria. See Peterson et al. (2004) for more details about respondent selection. Due to concerns about correlated errors and inadvertent double-counting of housing cost, income, and other information on households with two different nuclear families, this study excludes respondents who were in a “second” nuclear family.

HUD income limits are calculated for metropolitan areas and for non-metropolitan counties of every state and vary by size. Income limits for each fiscal year are available at: http://www.novoco.com/low_income_housing/facts_figures/income_limits.php.

Two thousand five hundred and forty-three RSAs fully completed the Adult module (Peterson et al. 2004: Table 2.8). The analytic sample is substantially smaller because of the exclusion of higher-income respondents, white and black immigrants (due to small sample size), and US- and foreign-born Asians and Pacific Islanders (due to small sample size and heterogeneity). Finally, the sample also excludes the few respondents who reported housing cost burdens of 100 % or more, based on concerns about the quality of their housing cost and/or income data.

Nearly 30 % of LAFAN’s respondents are missing one or more components of income (Peterson, Sastry, et al. 2004); the imputed income file is used when income data are missing.

About 90 % of the pooled sample live in households where the RSA or RSA/PCG is the household head, the head’s spouse/partner or the biological, step, adopted, or foster children of the head.

Imputed data for rent and mortgage payment from the imputed income file created for L.A.FANS (Bitler and Peterson 2004) were employed when housing cost data were missing.

L.A.FANS asked homeowners about the value of their home and asked homeowners with mortgages whether the mortgage amount included taxes or property insurance. For homeowners who reported that their mortgage payment excluded one or both of these items, their housing costs were increased to reflect both their mortgage and these other items based on alternate information. For homeowners who reported that their mortgage payment does not reflect property taxes, their housing costs also include annual property taxes of 1.16 %, the average property tax rate for Los Angeles County (Christensen and Esquivel 2010) based on the self-assessed value of their home provided to L.A.FANS. Housing costs for respondents who reported that their mortgage payments did not reflect homeowners’ insurance premiums were increased to include the average homeowners’ annual premium for California from US Census Bureau data for the year that the respondent was surveyed. Finally, housing costs for homeowners without mortgages are the sum of estimated property taxes and homeowners’ insurance based on the value of their home.

Approximately 76 % of Latinos in the final analytic sample identify as “Mexican/Mexicano” or “Mexican-American,” about the same proportion of Latinos identifying as Mexican in Los Angeles County (72 %) (US Census Bureau Table PCT011). The remainder indicate birth/descent in countries of Central America or other Latin American countries.

Correlation analyses and multicollinearity diagnostics, not shown, indicate that these two variables are weakly associated, thus reducing concerns that including both variables in the specification biases the results.

Ancillary analyses, not shown, indicate significant variation in this variable between authorized and unauthorized Latino immigrants. Alternative operationalizations of US experience were explored, such as continuous variable for years in the United States and percent of life spent in the United States (a la Greif 2009; McConnell 2012), neither are linked with cost burden.

L.A.FANS data include a home language variable, indicating whether the respondent and other household members speak English or Spanish. Ancillary analyses show that using survey language or home language produces nearly identical descriptive and multivariate results.

The mean ratio of housing costs to income for the pooled sample is 38.8 %, with unauthorized Latino immigrants having the highest allocation of income to housing, averaging 42.4 % of income on housing costs.

For example, unauthorized immigrants are not eligible for most transfer/public assistance programs, but their US-citizen children may be eligible for some programs. See Capps et al. (2002) for more information.

Immigrant respondents surveyed in L.A.FANS generally report long-term US residence; about 59 % arrived in the United States in the 1970s or the 1980s (Peterson et al. 2004: 212).

The general rule of thumb is that multicollinearity can be a serious problem when variance inflation factors (VIF) are 10 or higher (Menard 1995). Collinearity diagnostics for both models indicate VIF below 2.6 for every variable, with a mean VIF of 2.1 for the baseline model and 1.53 for the full model.

The specifications presented in Table 3 were carried out with a pooled sample of higher-income respondents. A comparison of the main effects of interest from those specifications, not shown, with the main effects presented in Table 3 reveals that the primary conclusions drawn in this paper are robust.

Taking the reciprocal of the odds ratio is another standard interpretation. For example, whites have odds that are 36 % lower than unauthorized Latino immigrants in the baseline model and 39 % lower in the full model (top panel, Table 3).

Additional logistic regression analyses (baseline and full model) with the pooled sample using alternative categorizations of Latinos that do not explicitly focus on nativity and legal status, such as a single indicator for Latino (versus white or black) or three indicators for Latino ethnicity (Mexican, Central American, Other Latino), reveal that neither one is significantly associated with housing cost burden.

Estimates of the fully standardized coefficients developed by Long and Freese (2003), not shown, indicate that homeownership and marital status are especially powerful predictors of the outcome.

Ancillary logistic regression analyses, not shown, using a continuous variable of education indicate that it is not independently associated with housing cost burden, net of covariates. Given the inclusion of Latino immigrants in the sample, operationalizing education using a binary indicator tapping into Latino immigrants’ average level of education is more useful.

The significant F-adjusted mean residual goodness-of-fit statistic suggests that the model lacks fit with the data (p = .0165). A simulation study suggests that the F-adjusted mean residual goodness-of-fit test has a higher rate of a Type I error with data comprised of small number of clusters (Archer et al. 2007). This result may be due to the relatively few clusters, sixty-five, in the L.A.FANS data.

Collinearity diagnostics for the immigrant-only analyses indicate VIFs of 1.0, 1.33, and 1.35 (first, second, and third columns, respectively, Table 5).

Supplementary analyses with a sample including higher-income respondents (not shown) indicate that in the baseline model, US-born Latinos are less likely to be cost burdened than both immigrant groups. Net of the same background variables used in the fully specified model in Tables 3 and 4, US-born Latinos of all income levels are equally likely to be housing cost burdened as authorized immigrants but less likely to cost burdened than unauthorized immigrants.

References

Abrego, L. (2006). ‘I can’t go to college because I don’t have papers’: Incorporation patterns of Latino undocumented youth. Latino Studies, 4(3), 212–231.

Alba, R. D., & Logan, J. R. (1992). Assimilation and stratification in the homeownership patterns of racial and ethnic groups. International Migration Review, 26(4), 1314–1341.

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Archer, K. J., & Lemeshow, S. (2006). Goodness-of-fit test for a logistic regression model estimated using survey sample data. The Stata Journal, 6(1), 97–105.

Archer, K. J., Lemeshow, S., & Hosmer, D. W. (2007). Goodness-of-fit tests for logistic regression models when data are collected using a complex sampling design. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 51(2007), 4450–4464.

Basolo, V., & Nguyen, M. T. (2009). Immigrants’ housing search and neighborhood conditions: A comparative analysis of housing choice voucher holders. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 11(3), 99–126.

Bender, S. W. (2010). Tierra y Libertad: Land, liberty, and Latino housing. New York: New York University.

Bernhardt, A., Milkman, R., et al. (2009). Broken laws, unprotected workers: Violations of employment and labor laws in America’s cities. New York: National Employment Law Project.

Bitler, M., & Peterson, C. (2004). LANFANS income and assets imputations: Description of imputed income/assets data for LAFANS wave 1. Santa Monica: RAND.

Blank, R., & Barr, M. S. (2009). Insufficient funds: Savings, assets, credit, and banking among low-income households. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Borjas, G. (2002). Homeownership in the immigrant population. Journal of Urban Economics, 52(3), 448–476.

Brennan, M. (2011). The impacts of affordable housing on education: A research summary. Washington, DC: National Housing Conference and the Center for Housing Policy Research.

Brennan, M., & Lipman, B. J. (2008). Stretched thin: The impact of rising housing expenses on America’s owners and renters. Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy.

Brown, H. (2011). Refugees, rights, and race: How legal status shapes Liberian immigrants’ relationship with the state. Social Problems, 58(1), 144–163.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2009). Consumer expenditures—2008. Table A. Average annual expenditures and characteristics of all consumer units and percent changes, consumer expenditure survey, 2006–2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor.

Capps, R., Ku, L., et al. (2002). How are immigrants faring after welfare reform? Preliminary evidence from Los Angeles and New York City—Final report. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Charles, C. Z. (2006). Won’t you be my neighbor? Race, class, and residence in Los Angeles New York. NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Chavez, L. (1990). Coresidence and resistance: Strategies for survival among undocumented Mexicans and central Americans in the United States. Urban Anthropology, 19(1–2), 31–61.

Chavez, L. (1992). Shadowed lives: Undocumented Immigrants in American Society. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College.

Chavez, L. (1996). Borders and bridges: Undocumented immigrants from Mexico and the United States. In S. Pedraza & R. G. Rumbaut (Eds.), Origins and destinies: Immigration, race, and ethnicity in America (pp. 250–262). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Chavez, J. M., & Provine, D. M. (2009). Race and the response of state legislatures to unauthorized immigrants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623(1), 78–92.

Chi, P. S. K., & Laquatra, J. (1998). Profiles of housing cost burden in the United States. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 19(2), 175–193.

Christensen, K., & Esquivel, P. (2010). Bell property tax rate second-highest in LA County. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times.

Clark, W. A. V. (2003). Immigrants and the American dream: Remaking the middle class. New York: Guilford Press.

Clark, W. A. V., & Ledwith, V. (2006). Mobility, housing stress and neighborhood contexts: Evidence from Los Angeles. Environment and Planning A, 38(6), 1077–1093.

Clark, W. A. V., & Ledwith, V. (2007). How much does income matter in neighborhood choice? Population Research and Policy Review, 26(2), 145–161.

Cohen, R. (2011). The impacts of affordable housing on health: A research summary. Washington, DC: National Housing Conference and the Center on Housing Policy.

Combs, E. R., & Park, S. (1994). Housing affordability among elderly female heads of household in nonmetropolitan areas. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 15(4), 317–328.

Cort, D. (2012). Reexamining the ethnic hierarchy of locational attainment: Evidence from Los Angeles. Social Science Research, 40(6), 1521–1533.

Coulson, N. E. (1999). Why are Hispanic and Asian-American homeownership rates so low? Immigration and other factors. Journal of Urban Economics, 45(2), 209–227.

De Genova, N. (2004). The legal production of Mexican/migrant “illegality”. Latino Studies, 2(2), 160–185.

DeVaney, S. A., Chiremba, S., et al. (2004). Life cycle stage and housing cost burden. Financial Counseling & Planning, 15(1), 31–39.

Donato, K. M., & Armenta, A. (2011). What we know about unauthorized migration? Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 529–543.

Elder, G. H., Jr., Johnson, M. K., et al. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course. New York City: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Elmelech, Y. (2004). Housing inequality in New York City: Racial and ethnic disparities in homeownership and shelter-cost burden. Housing, Theory, and Society, 21(4), 163–175.

Ennis, S. R., Ríos-Vargas, M., et al. (2011). The Hispanic population: 2010. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Espenshade, T. J. (1995). Unauthorized Immigration to the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 195–216.

Espino, R., & Franz, M. M. (2002). Latino phenotype discrimination revisited: The impact of skin color on occupational status. Social Science Quarterly, 83(2), 612–623.

Farley, R. (2001). Metropolises of the multi-city study of urban inequality: Social, economic, demographic, and racial issues in Atlanta, Boston, Detroit, and Los Angeles. In A. O’Connor, C. Tilly, & L. D. Bobo (Eds.), Urban inequality: Evidence from four cities (p. 34). New York City: Russell Sage.

Fortuny, K., Capps, R., et al. (2007). The characteristics of unauthorized immigrants in California, Los Angeles County, and the United States. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Frank, R., Akresh, I. R., et al. (2010). Latino Immigrants and the US racial order: How and where do they fit in? American Sociological Review, 75(3), 378–401.

Frank, R., & Bjornstrom, E. E. S. (2011). A tale of two cities: Residential context and risky behavior among Latino adolescents in Los Angeles and Chicago. Health & Place, 17(1), 67–77.

Goldman, D. P., Smith, J. P., et al. (2005). Legal status and health insurance among immigrants. Health Affairs, 24(6), 1640–1653.

Gonzales, R. G., & Chavez, L. R. (2012). “Awakening to a nightmare”: Abjectivity and illegality in the lives of undocumented 1.5 generation Latino immigrants in the United States. Current Anthropology, 53(3), 255–281.

Gonzalez, R. (2011). Learning to be illegal: Undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review, 76(4), 602–619.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

Greif, M. J. (2009). Neighborhood attachment in the multiethnic metropolis. City & Community, 8(1), 27–45.

Guzmán, B., (2001). The Hispanic population: Census 2000 brief. C2KBR/01-3. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Hall, M., Greenman, E., et al. (2010). Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants. Social Forces, 89(2), 491–513.

Hinojosa Ojeda, R., Jacquez, A., et al. (2009). The end of the American dream for blacks and Latinos: How the home mortgage crisis is destroying black and Latino wealth, jeopardizing America’s future prosperity and how to fix it. Los Angeles, CA: William C. Velasquez Institute.

Hoefer, M., Rytina, N., et al. (2010). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2009. Washington, DC: Office of Immigration Statistics, US Department of Homeland Security.

Hogarth, J. M., Anguelov, C. E., et al. (2005). Who has a bank account? Exploring changes over time, 1989–2001. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 26(1), 7–30.

Jewkes, M. D., & Delgadillo, L. M. (2010). Weaknesses of housing affordability indices used by practitioners. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 21(1), 43–52.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2008). America’s rental housing: The key to a balanced national policy. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2009). The state of the nation’s housing 2009. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2011). State of the nation’s housing: 2011. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2012). The state of the nation’s housing 2012. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Krivo, L. J. (1995). Immigrant characteristics and Hispanic–Anglo housing inequality. Demography, 32(4), 599–615.

Krivo, L. J., & Kaufman, R. L. (2004). Housing and wealth inequality: Racial-ethnic differences in home equity in the United States. Demography, 41(3), 585–605.

Kutty, N. K. (2005). A new measure of housing affordability: Estimates and analytical results. Housing Policy Debate, 16(1), 113–142.

Lipman, B. (2003). America’s newest working families: Cost, crowding, and conditions for immigrants. Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy.

Lipman, B. (2005). Something’s gotta give: Working families and the cost of housing. Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2003). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Los Angeles Housing Crisis Task Force. (2000). In short supply: Recommendations of the Los Angeles housing crisis task force. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Housing Department.

Luea, H. (2008). The impact of financial help and gifts on housing demand and cost burdens. Contemporary Economic Policy, 26(3), 420–432.

Mackun, P. J., & Wilson, S. (2011). Population distribution and change: 2000 to 2010. Washington, DC: USC Bureau, C2010BR-01, US Department of Commerce.

Massey, D. S., & Bartley, K. (2005). The changing legal status distribution of immigrants: A caution. International Migration Review, 39(2), 469–484.

Massey, D. S., & Pren, K. A. (2012). Origins of the new Latino underclass. Race and Social Problems, 4(1), 5–17.

McArdle, N., & Mikelson, K. S. (1994). The new immigrants: Demographic and housing characteristics. Working Paper. Cambridge: Joint Center for Housing Studies.

McConnell, E. D. (2012). House poor in Los Angeles: Examining patterns of housing-induced poverty by race, nativity, and legal status. Housing Policy Debate, 22(4), 605–631.

McConnell, E. D., & Akresh, I. R. (2010). Housing cost burden and new lawful immigrants in the United States. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(2), 143–171.

McConnell, E. D., & Marcelli, E. A. (2007). Buying into the American dream? Mexican immigrants, legal status, and homeownership in Los Angeles County. Social Science Quarterly, 88(1), 199–221.

Menard, S. (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis. Sage university series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Menjívar, C. (2006). Liminal legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ lives in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 111(4), 999–1037.

Menjívar, C. (2011). The power of the law: Central Americans’ legality and everyday life in Phoenix, Arizona. Latino Studies, 9(4), 377–395.

Myers, D., & Lee, S. W. (1998). Immigrant trajectories into homeownership: A temporal analysis of residential assimilation. International Migration Review, 32(3), 593–625.

Myers, D., Painter, G., et al. (2005). Regional disparities in homeownership trajectories: Impacts of affordability, new construction, and immigration. Housing Policy Debate, 16(1), 53–83.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2011). Immigration-related laws and resolutions in the states (Jan. 1–Dec. 7, 2011). Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures.

Nelson, A. A. (2010). Credit scores, race, and residential sorting. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(1), 39–68.

Oh, D.-H. (1995). Households with rent burdens: Impact on other spending and factors related to the probability of having a rent burden. Financial Counseling and Planning, 6, 139–147.

Oliveri, R. C. (2009). Between a rock and a hard place: Landlords, Latinos, anti-illegal immigrant ordinances, and housing discrimination. Vanderbilt Law Review, 62(1), 55–124.

Osili, U. O., & Paulson, A. (2004). Immigrant-native differences in financial market participation. Chicago: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Owens, C., & Tegeler, P. (2007). Housing cost burden as a civil rights issue: Revisiting the 2005 American community survey data. Washington, DC: Poverty & Race Research Action Council.

Painter, G., Gabriel, S., et al. (2001). Race, immigrant status, and housing tenure choice. Journal of Urban Economics, 49(1), 150–167.

Passel, J. S. (2006). The size and characteristics of the unauthorized migrant population in the US: Estimates based on the March 2005 current population survey. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Pebley, A. R., & Sastry, N. (2004). The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, field interviewer manual. DRU-2400/5-1-LAFANS. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Peterson, C. E., Pebley, A. R., et al. (2007). The Los Angeles neighborhood services and characteristics database: Codebook. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Peterson, C. E., Sastry, N., et al. (2004). The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey codebook. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Pew Hispanic Center. (2008). A statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Portes, A., Fernández-Kelly, P., et al. (2005). Segmented assimilation on the ground. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(6), 1000–1040.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 530, 74–96.

Rodríguez, H., Sáenz, R., et al. (Eds.). (2008). Latinas/os in the United States: Changing the face of America. New York: Springer.

Rosenbaum, E., & Friedman, S. (2007). The housing divide: How generations of immigrants fare in New York’s housing market. New York City: New York University Press.

Sastry, N., Ghosh-Dastidar, B., et al. (2006). The design of a multilevel survey of children, families, and communities: The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Social Science Research, 35(4), 1000–1024.

Sastry, N., & Pebley, A. R. (2003). Non-response in the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Labor and Population Program Working Paper. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Schill, M. H., Friedman, S., et al. (1998). The housing conditions of immigrants in New York City. Journal of Housing Research, 9(2), 201–235.

Simms, M. C., Fortuny, K., et al. (2009). Racial and ethnic disparities among low-income families. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Standish, K., Nandi, V., et al. (2010). Household density among undocumented Mexican immigrants in New York City. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 12(3), 310–318.

Stone, M. E. (1993). Shelter poverty: New ideas on housing affordability. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Stone, M. E. (2006). What is housing affordability? The case for the residual income approach. Housing Policy Debate, 17(1), 151–184.

Suchan, T., Perry, M. J., et al. (2007). Census atlas of the United States. Washington, DC: S. CENSR-29, US Census Bureau.

Taylor, P., Lopez, M. H., et al. (2011). Unauthorized immigrants: Length of residency, patterns of parenthood. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Telles, E. E., & Ortiz, V. (2008). Generations of exclusion: Mexican Americans, assimilation, and race. New York: Russell Sage.

Toussaint-Comeau, M., & Rhine, S. L. W. (2004). Tenure choice with location selection: The case of Hispanic neighborhoods in Chicago. Contemporary Economic Policy, 22(1), 95–110.

US Census Bureau. Table “P007. Hispanic or Latino by race: 2000.” United States, retrieved October 9, 2012, from American FactFinder; http://factfinder.census.gov.

US Census Bureau. Table “PCT011. Hispanic or Latino by specific origin [31].” Los Angeles County and United States. Retrieved September 9, 2012, from American FactFinder; http://factfinder.census.gov.

US Census Bureau. Tables “HCT048B, HCT048H, HCT048I. Median selected monthly owner costs as a percentage of household income in 1999 and mortgage status. Los Angeles County. Retrieved August 1, 2011 from American FactFinder; http://factfinder.census.gov.

US Census Bureau. Table “HCT052. Median gross rent (dollars).” Los Angeles County. Retrieved August 1, 2011 from American FactFinder; http://factfinder.census.gov.

US Census Bureau. Table “HCT063. Household Income in 1999 by gross rent as a percentage of household income in 1999.” Los Angeles County. Retrieved August 1, 2011 from American FactFinder; http://factfinder.census.gov.

Williams, L. (2012). An annual look at the housing affordability challenges of America’s working households. Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy and National Housing Conference.

Woldoff, R. A., & Ovadia, S. (2009). Not getting their money’s worth: African American disadvantages in converting income, wealth, and education into residential quality. Urban Affairs Review, 45(1), 66–91.

Zhou, M., Lee, J., et al. (2008). Success attained, deterred, and denied: Divergent pathways to social mobility in Los Angeles’s new second generation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 620, 37–61.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Grant R03 HD058915-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Development. The author appreciates the research assistance of Tun Lin Moe and the suggestions of the editor and an anonymous reviewer on earlier versions of the manuscript. All errors of fact and interpretation are the sole responsibility of the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A correction to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12552-013-9101-2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McConnell, E.D. Who has Housing Affordability Problems? Disparities in Housing Cost Burden by Race, Nativity, and Legal Status in Los Angeles. Race Soc Probl 5, 173–190 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-013-9086-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-013-9086-x