Abstract

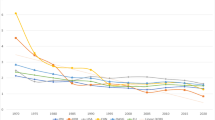

Previous research has found that there is a good deal of stability in departmental prestige, but has not considered its long-term dynamics. This paper investigates a hypothesis implied by some accounts in the sociology of science and organizational theory: that there will be a permanent component of prestige associated with the department or university. The data are the ratings of graduate departments of sociology between 1965 and 2007 using a measure of prestige constructed from hiring patterns. There is no evidence of a permanent component for individual departments, but there is evidence of a permanent difference between departments in “elite” universities and those in other universities. Despite change in rankings within each group, the difference between the groups remained constant over the period. That is, there appear to be enduring barriers that limit the mobility of individual departments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The hypothesis of enduring differences cannot be tested by including a separate dummy variable for each department, since this procedure produces biased estimates (Hsiao 1986, pp. 73–6).

There is no generally accepted terminology; some studies (e. g., Podolny 2005) use “status” to refer to similar measures of network position.

Several studies, including Keith and Babchuk (1998), Paxton and Bollen (2003), and Burris (2004) have considered the relationship between prestige and research productivity and found some systematic departures. That is, they imply that to some extent reputation reflects “ascription” rather than “achievement.” Podolny (2005) argues that status differences will generally exaggerate real differences in quality—that is, the highest-ranking organizations will be overrated and the lowest-ranking ones will be underrated. This paper will not consider the extent to which differences in prestige are deserved—it simply regards them as a fact.

We counted tenured or tenure-track faculty whose primary appointment was in the sociology department—emeritus faculty and courtesy appointments were excluded. When sociology was combined with another field in a single department (most often anthropology), we attempted to identify and exclude faculty from the other field. Members of a sociology department with graduate training in another field were included. It would be very difficult to identify such people systematically, and some may have worked closely with sociologists during their graduate education. Therefore, we counted all as sociologists rather than risk introducing selection bias by excluding some based on personal impressions. In the earlier years, a number of faculty did not have a PhD, either because they were hired when still working on their dissertations or because their careers began before the degree became essential. For those cases, we counted the last institution at which they were known to have done graduate study in sociology—the department at which they received a master’s degree or began their dissertation. We excluded those with degrees from professional schools or from universities outside the United States.

The missing cases may result from omissions in the database, degrees from universities outside the United States, or degrees that were awarded under another name.

The measures are based on all members of the faculty, not just recent hires. Therefore, they build in some inertia—departments continue to get credit for graduates from several decades ago. However, over the entire period there was almost complete turnover in faculty. Out of approximately 2,000 faculty members in 2007, only 27 had been on the faculty at graduate departments in 1965, and only 9 of those remained at the same institution. Nevertheless, the correlation between 1965 prestige and 2007 prestige was 0.828.

The other founding members of the AAU were Clark and Catholic Universities, neither of which are members today. Clark granted a few doctoral degrees in sociology, but never offered a regular program; see note 8 on Catholic University.

Keniston’s list also included Catholic University, which was established as an exclusively graduate institution and produced a large number of doctorates through the 1950s. However, it focused on supplying faculty for other Catholic universities, and the Keniston survey did not rank any of its departments among the leaders.

The first group includes Berkeley, Chicago, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Princeton, Stanford, Wisconsin, and Yale; the second includes Duke, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, North Carolina, Northwestern, NYU, Ohio State, Texas, UCLA, and Washington (Seattle). Catttell’s (1906) list of leading employers of scientists also included MIT, which has never offered a PhD in sociology. The next two universities on his list were Minnesota and Ohio State.

In more detailed analysis we found one systematic departure from the pattern: departments are more likely to hire their own graduates. Omitting these cases does not produce significant changes in the relative position of departments, so the reported results count all placements. It is worth noting, however, that the tendency became much weaker over the period: in 1965, 15% of all faculty members in graduate departments were employed at the department from which they had earned their PhD; in 2007, only 4% were.

The most recent NRC rankings (Ostriker et al. 2010) are quite different from previous ones, as well as from the 2007 rankings of second-order placements. However, the latest NRC rankings represent weighted averages of a large number of objective characteristics rather than the results of a survey. The most rankings by second-order placements are highly correlated with the 2009 rankings by U. S. News (2011), which are based on a survey. Thus, the changes in NRC rankings seem to reflect changes in methodology rather than changes in the world.

The NRC reputation rankings are based on current faculty, while second-order placements include all graduates. As a result, the reputational rankings are more sensitive to more recent changes, whether for better or for worse. This difference can plausibly account for most of the discrepancies involving high-ranked departments.

The variance of the number of second-order placements is proportional to the mean, as is often the case with counts. The square root transformation eliminates the relationship between the mean and variance, and also makes the relationships with other variables more nearly linear. See Bartlett (1947) for more discussion of the square root transformation.

Berkeley and Johns Hopkins did not establish departments of sociology until the 1950s.

References

Allison, P. D., & Long, J. S. (1990). Departmental effects on scientific productivity. American Sociological Review, 55, 469–478.

Amir, R., & Knauff, M. (2005). Ranking economics departments worldwide on the basis of PhD placement. CORE Discussion Paper 2005–41. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Université de Louvain.

Baldi, S. (1994). Changes in the stratification structure of sociology, 1964–92. American Sociologist, 25, 28–43.

Bartlett, M. S. (1947). The use of transformations. Biometrics, 3, 39–52.

Burris, V. (2004). The academic caste system: hierarchies in PhD exchange networks. American Sociological Review, 39, 239–264.

Cattell, J. M. (1906). A statistical study of american men of science. III. The distribution of american men of science. Science, 23, 732–742.

Crane, D. (1965). Scientists at major and minor universities: a study of productivity and recognition. American Sociological Review, 30, 699–714.

DiPrete, T. A., & Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297.

Fogarty, T. J., & Saftner, D. V. (1993). Academic department prestige: a new measure based on the doctoral student labor market. Research in Higher Education, 34, 427–449.

Graham, H. D., & Diamond, N. (1997). The rise of american research universities: Elites and challengers in the postwar period. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Han, S.-K. (2003). Tribal regimes in academia: a comparative analysis of market structure across disciplines. Social Networks, 25, 251–280.

Hanneman, R. A. (2001). The prestige of Ph.D. granting departments of sociology: a simple network approach. Connections, 24, 68–77.

Hsiao, C. (1986). Analysis of panel data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hughes, R. M. (1925). A study of the graduate schools of America. Miami: Miami University.

Hughes, R. M. (1934). Report of committee on graduate instruction. The Educational Record, 15, 192–234.

Hurlbert, B. M. (1976). Status and exchange in the profession of anthropology. American Anthropologist (new series), 78, 272–284.

Jones, L. V., Lindzey, G., & Coggeshall, P. E. (Eds.). (1982). An assessment of research-doctorate programs in the United States. Washington: National Academy Press.

Keith, B. (1994). The institutional structure of eminence: alignment of prestige among Intra-University academic departments. Sociological Focus, 27, 363–381.

Keith, B., & Babchuk, N. (1998). The quest for institutional recognition. Social Forces, 76, 1495–1533.

Keniston, H. (1959). Graduate study and research in the arts and sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kerr, C. (1991). The new race to be Harvard or Berkeley or Stanford. Change, 23, 8–15.

Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159, 56–63.

Merton, R. K. (1988). The Matthew effect in science, II: cumulative advantage and the symbolism of intellectual property. Isis, 79, 606–623.

National Research Council. (1995). Research-doctorate programs in the United States: Continuity and change. Washington: National Academy of Sciences.

Ostriker, J. P., Holland, P. W., Kuh, C., & Voytuk, J. A. (2010). A data-based assessment of research-doctorate programs in the United States. Washington: National Academies Press.

Palacios-Huerta, I., & Volij, O. (2004). The measurement of intellectual influence. Econometrica, 72, 963–977.

Paxton, P., & Bollen, K. A. (2003). Perceived quality and methodology in graduate department ratings. Sociology of Education, 76, 71–88.

Podolny, J. (2005). Status signals: A sociological study of market competition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Schmidt, B. M., & Chingos, M. M. (2007). Ranking doctoral programs by placement: a new method. PS: Political Science and Politics, 40, 523–529.

U. S. News and World Report. (2011). America’s best graduate schools. Washington: U. S. News and World Report.

Weber, M. (1946). In H. H. Gerth & C. Wright Mills (Eds.), From Max Weber: Essays in scoiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weeber, S. C. (2006). Elite versus mass sociology: an elaboration on sociology’s academic caste system. American Sociologist, 37, 50–67.

Acknowledgments

We thank several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weakliem, D.L., Gauchat, G. & Wright, B.R.E. Sociological Stratification: Change and Continuity in the Distribution of Departmental Prestige, 1965–2007. Am Soc 43, 310–327 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-011-9133-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-011-9133-2