Abstract

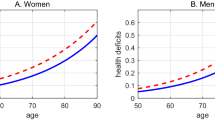

The gradual changes in cohort composition that occur as a result of selective mortality processes are of interest to all aging research. We present the first illustration of changes in the distribution of specific cohort characteristics that arise purely as a result of selective mortality. We use data on health, wealth, education, and other covariates from two cohorts (the AHEAD cohort, born 1900–1923 and the HRS cohort, born 1931–1941) included in the Health and Retirement Survey, a nationally representative panel study of older Americans spanning nearly two decades (N = 14,466). We calculate sample statistics for the surviving cohort at each wave. Repeatedly using only baseline information for these calculations so that there are no changes at the individual level (what changes is the set of surviving respondents at each specific wave), we obtain a demonstration of the impact of mortality selection on the cohort characteristics. We find substantial changes in the distribution of all examined characteristics across the nine survey waves. For instance, the median wealth increases from about $90,000 to $130,000 and the number of chronic conditions declines from 1.5 to 1 in the AHEAD cohort. We discuss factors that influence the rate of change in various characteristics. The mortality selection process changes the composition of older cohorts considerably, such that researchers focusing on the oldest old need to be aware of the highly select groups they are observing, and interpret their conclusions accordingly.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams, P., Hurd, M. D., McFadden, D. L., Merrill, A., & Ribeiro, T. (2004). Healthy, wealthy, and wise? Tests for direct causal paths between health and socioeconomic status. In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Perspectives on the economics of aging (pp. 415–526). Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Coale, A., & Kisker, E. E. (1986). Mortality crossovers: Reality or bad data? Population Studies, 40, 389–401.

DiPrete, T. A., & Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297.

Dupre, M. E. (2008). Educational differences in health risks and illness over the life course: A test of cumulative disadvantage theory. Social Science Research, 37(4), 1253–1266.

Dupre, M. E., Franzese, A. T., & Parrado, E. A. (2006). Religious attendance and mortality: Implications for the black–white mortality crossover. Demography, 43(1), 141–164.

Elo, I. T., & Drevenstedt, G. L. (2002). Educational differences in cause-specific mortality in the United States. Yearbook of Population Research in Finland, 38, 37–54.

Elo, I. T., Martikainen, P. T., & Smith, K. P. (2006). Socioeconomic differentials in mortality in Finland and the United States: The role of education and income. European Journal of Population, 22(2), 179–203.

Ferraro, K. F., & Farmer, M. M. (1996). Double jeopardy, aging as leveler, or persistent health inequality? A longitudinal analysis of white and black Americans. Journal of Gerontology Social Sciences, 51B(6), S319–S328.

Ferraro, K. F., Shippee, T. P., & Schafer, M. H. (2009). Cumulative inequality theory for research on aging and the life course. In V. L. Bengtson, D. Gans, N. M. Putney, & M. Silverstein (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (pp. 413–433). New York: Springer.

Groves, R. M., & Couper, M. P. (1998). Nonresponse in household interview surveys. New York: Wiley.

Hodes, R. J., & Suzman, R. (2007). Growing older in America: The health and retirement study. Bethesda: National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

House, J. S., Kessler, R. C., Herzog, A. R., Mero, R. P., Kinney, A. M., & Breslow, M. J. (1990). Age, socioeconomic status, and health. The Milbank Quarterly, 68(3), 383–411.

House, J. S., Lepkowski, J. M., Kinney, A. M., Mero, R. P., Kessler, R. C., & Herzog, A. R. (1994). The social stratification of aging and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35(3), 213–234.

Johnson, N. E. (2000). The racial crossover in comorbidity, disability, and mortality. Demography, 37(3), 267–283.

Juster, F. T., & Suzman, R. (1995). An overview of the health and retirement study. The Journal of Human Resources, 30(Supplement), S7–S56.

Keyfitz, N. (1985). Heterogeneity and selection in population analysis. In Applied mathematical demography. New York: Springer.

Korn, E. L., & Graubard, B. I. (1999). Analysis of health surveys. New York: Wiley.

Kurland, B. F., Johnson, L. L., Egleston, B. L., & Diehr, P. H. (2009). Longitudinal data with follow-up truncated by death: Match the analysis method to research aims. Statistical Science, 24(2), 211–222.

Lauderdale, D. S. (2001). Education and survival: Birth cohort, period, and age effects. Demography, 38(4), 551–561.

Lynch, S. M. (2003). Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: A hierarchical approach. Demography, 40(2), 309–331.

Manton, K. G. (1999). Dynamic paradigms for human mortality and aging. Journal of Gerontology Biological Sciences, 54(6), B247–B254.

Manton, K. G., Poss, S. S., & Wing, S. (1979). The black/white mortality crossover: Investigation from the perspective of the components of aging. The Gerontologist, 19(3), 291–300.

Masters, R. (2012). Uncrossing the U.S. black–white mortality crossover: The role of cohort forces in life course mortality risk. Demography, 49(3), 773–796.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2008). Education and self-rated health: Cumulative advantage and its rising importance. Research on Aging, 30(1), 93–122.

Montez, J. K., Hummer, R. A., & Hayward, M. D. (2012). Educational attainment and adult mortality in the United States: A systematic analysis of functional form. Demography, 49(1), 315–336.

RAND Corp. (2011). The RAND HRS Data (Version L) 2012. http://www.rand.org/labor/aging/dataprod/hrs-data.html. Accessed 30 Mar 2012.

Trussell, J., & Richards, T. (1985). Correcting for unmeasured heterogeneity in hazard models using the heckman-singer procedure. In N. B. Tuma (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 242–276). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Trussell, J., & Rodríguez, G. (1990). Heterogeneity in demographic research. In J. Adams, D. A. Lam, A. I. Hermalin, & P. E. Smouse (Eds.), Convergent issues in genetics and demography (pp. 111–132). New York: Oxford University Press.

Vaupel, J. W. (1988). Inherited frailty and longevity. Demography, 25(2), 277–287.

Vaupel, J. W., Manton, K. G., & Stallard, E. (1979). The impact of heterogeneity in individual frailty on the dynamics of mortality. Demography, 16(3), 439–454.

Vaupel, J. W., & Yashin, A. I. (1985). Heterogeneity’s ruses: Some surprising effects of selection on population dynamics. The American Statistician, 39(3), 176–185.

Vaupel, J. W., & Zhang, Z. (2010). Attrition in heterogeneous cohorts. Demographic Research, 23(26), 737–748.

Willson, A. E., Shuey, K. M., & Elder, G. H. (2007). Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1886–1924.

Zajacova, A., Goldman, N., & Rodríguez, G. (2009). Unobserved heterogeneity can confound the effect of education on mortality. Mathematical Population Studies, 16(2), 153–173.

Zajacova, A., & Hummer, R. A. (2009). Gender differences in education gradients in all-cause mortality for white and black adults born 1906–1965. Social Science and Medicine, 69(4), 529–537.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Karas-Montez, Robert A. Hummer, Scott M. Lynch, and Deborah Lowry for helpful suggestions on an early version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zajacova, A., Burgard, S.A. Healthier, Wealthier, and Wiser: A Demonstration of Compositional Changes in Aging Cohorts Due to Selective Mortality. Popul Res Policy Rev 32, 311–324 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9273-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9273-x