Abstract

While considerable research focuses on the anti-poverty and labor supply effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), relatively little is known about the program’s influence on marriage and divorce decisions. Furthermore, nearly all work in this area uses stock measures of marital status derived from survey data. In this paper, I draw upon Vital Statistics data between 1977 and 2004 to construct a transition-based measure of marriage and divorce rates. Flows into and out of marriage are advantageous because they are more likely to capture the immediate impact of policy changes. Controlling for state-level characteristics and sources of unobserved heterogeneity, I find that increases in the EITC are associated with reductions in new marriages, although the estimated effect is economically small. I find no relationship between the EITC and new divorces. These results are robust to alternative estimation strategies, data restrictions, and the inclusion of additional policy and demographic controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, a 1996 study by the U.S. General Accounting Office (1996) found at least 59 provisions that reward or penalize marriage. Since the date of this study, several important pieces of tax legislation were passed that have implications for non-neutrality. For example, the 1997 Taxpayer Relief Act created the child tax credit, and the 2001 Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA) altered the EITC (among other things) to alleviate marriage penalties in the tax code.

Additional income from interest, dividends, and capital gains cannot exceed $2,600.

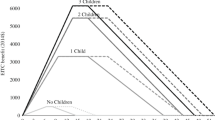

The creation of a separate EITC schedule for childless workers in 1993 is another important design feature. With a phase-in rate of 7.65%, its maximum credit is substantially smaller than those for one- and multiple-child families. Nevertheless, this EITC was created to mitigate the marriage and fertility distortions imbedded in the original design.

I focus on Texas and Wisconsin for several reasons. Since Texas does not have a state income tax, it illustrates a pure federal EITC effect. Wisconsin, other the other hand, has relatively high state income taxes but also has one of the most generous state EITC programs. See details in text about the Wisconsin program. Therefore, these states allow one to examine the ways in which state EITCs likely amplify the marriage incentives embedded in the federal credit.

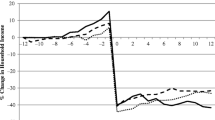

These simulations, which use NBER’s TAXSIM model, are conducted in the following manner. All families take the relevant standard deduction and are assumed to have zero unearned income or child care expenses. Unmarried women with children file as “head of household” and claim their children as dependents, unmarried men file as “single”, and married couples file as “married filing jointly.” All dollars amounts are adjusted to reflect 2004 prices. Positive numbers in Fig. 1 indicate marriage subsidies, and negative numbers indicate marriage penalties.

Critical to the EITC is the model’s extension to account for cohabitation among partners (Clarkberg et al. 1995; Ellwood 2000; Ellwood and Jencks 2001). See Acs and Maag (2005) for a discussion of the marriage subsidies and penalties that arise in the tax and transfer system for cohabitating couples.

It is important to note that several other theoretical models have rendered important insights on marriage and divorce decisions. For example, search models have been used to examine whether the quality of local marriage markets influences marriage decisions generally and the extent of assortive mating specifically (Lichter et al. 1995). Other studies focus on the importance of individual’s observable characteristics (e.g., race and ethnicity and educational attainment) in driving marriage patterns (Blackwell and Lichter 2000).

A large literature examines the impact of various components of the income tax system on marital behavior. See Alm and Whittington (1995, 1997), Dickert-Conlin (1999), and Whittington and Alm (1997) for a sampling of work on this topic. This work generally finds that taxes affect both the decision to enter and end a marriage, as well as the timing of these decisions. Also relevant to this study is the large literature on the effects of traditional cash assistance programs on marriage and living arrangements. Moffitt’s (1998) review concludes that there appears to be a small positive relationship between welfare benefits and female headship. However, as noted in Moffitt (1994) and Hoynes (1997), much if not all of the positive effect is driven by unobserved heterogeneity. Including fixed effects in such models renders the welfare effect insignificant. More recent evidence by Fitzgerald and Ribar (2004) and Dickert-Conlin and Houser (1999) confirm findings from earlier work. Another cluster of studies examines in the impact of welfare reform on marriage, divorce, and headship decisions, with some finding positive effects of reform (Schoeni and Blank 2000), others finding negative effects (Bitler et al. 2004; Horvath-Rose and Peters 2001), and still others finding inconsistent or insignificant effects (Fitzgerald and Ribar 2004; Ellwood 2000; Kaushal and Kaestner 2001).

I omit 1975 and 1976 from the analysis because the data used for the denominator in the marriage and divorce rates (number of unmarried and married women, respectively, ages 15 and over) are drawn from the CPS, which does not have these data available for these years.

California is missing new marriages for 1991, and Oklahoma is missing these data for 2001–2003. Divorce data are missing for the following state-years: California (1991–2004), Colorado (1995–2000), Georgia (2004), Hawaii (2003–2004), Indiana (1991–2004), Louisiana (1991–2004), Nevada (1991–1993), and Oklahoma (2001–2003).

Using an unbalanced panel of state-years causes a few concerns. If states with missing marriage/divorce data are trending differently, it would be difficult to distinguish the impact of federal EITC expansions or the implementation of a state EITC from other state-specific factors. Moreover, a number of states are missing information during a period when important expansions to the federal credit were implemented (1991–1993; 1991–2004; 1995–2000). In a later section, however, I test the sensitivity of the main results by estimating the model on the unbalanced panel of states.

A Wooldridge (2002) test of no serial correlation in panel data yields a highly significant F-statistic in the marriage (F = 34.41) and divorce (F = 27.26) regressions. The Prais-Winsten regression assumes that the autocorrelation follows an AR(1) process that is common across all states. Standard errors in these models are also corrected for heteroskedasticity.

In particular, the EITC is typically paid by the IRS in the calendar year after the tax year in which it was earned (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 1999). Also, there are a number of mechanisms used by states to slow the decision-making process prior to a marriage or divorce. For example, three states (Arizona, Arkansas, and Louisiana) have covenant marriage options, which stipulate that couples must receive counseling before seeking a divorce. A number of states specify a waiting period after a divorce before an individual can re-marry. There are also so-called “cooling off” periods between the time a divorce is petitioned and when it is actually granted by a judge. These waiting periods vary dramatically by state, and can range from no statutory requirement to 18 months (Arkansas, Connecticut, and New Jersey). On the other hand, states have also passed no fault divorce laws, which allow partners to seek a divorce without gaining the consent of the spouse. See research by Friedberg (1998) and Wolfers (2006) for an evaluation of the impact of no fault laws on divorce. To examine the robustness of the main results to the choice of lag structure, I experiment with a one-period lag of the EITC. Results from this specification are discussed in a subsequent section. There are, however, reasons to be believe that a 2-year lag structure is not long enough. Low-income couples are more likely to separate for substantial periods, and hence stop filing taxes jointly, before a divorce is formalized. It is difficult to know whether an EITC-induced divorce would catalyze a long separation period, but suffice it to say that a 2-year lag on the EITC may not pick up all divorces that occur after a long-term separation. I thank an anonymous referee for pointing out this possibility.

The potential endogeneity of the EITC is a manifestation of the more general policy endogeneity problem. The concern here is that the timing of EITC expansions coincides with, or responds to, broader societal trends that influence marriage and divorce propensities. For example, if states that enact EITC programs to reduce poverty or strengthen work incentives have populations with different underlying tastes for marriage, then EITC policies will be correlated with these unobserved preferences and the estimated effect of the credit on marriage and divorce will be biased. As noted in the text, that the EITC is primarily a federal program, however, makes policy endogeneity less likely.

To calculate this number, I regressed the log of the new marriage (divorce) rate on a linear time trend (with robust standard errors and weighted by the number of women ages 15 and over).

Nevada’s new marriage rate exceeded one between 1977 and 1980, but remained far above the national average after that. Summary statistics for the new marriage rate after dropping Nevada are the following: mean = 0.053; SD = 0.016; minimum = 0.014; maximum = 0.137.

The impact of a one-dollar increase in the EITC is calculated by the following: [β(unmarried)/EITC], where β is the parameter estimate from Table 3, Model 2 (divided by 1,000); unmarried is the number unmarried women ages 15 and over, averaged over the observation period; and EITC is the maximum credit for a family with two or more children, averaged over the observation period. See the notes in Table 2 for summary statistics associated with unmarried and married.

As noted by Bitler et al. (2004) and Blank (2002), the identification strategy for TANF is weaker than for the waiver variable. TANF was phased-in by all states over a relatively short period (September 1996 to January 1998, or 16 months), while welfare waivers were experimented with by a smaller number of states over 5-year period (1992–1996). Therefore, the effect of TANF is identified by substantially smaller cross-state variation in the timing of implementation. It is also important to note that both welfare reform variables roll several policy reforms into a one-dimensional variable, and that TANF, in particular, is likely to generate different impacts on marriage and divorce if one were to estimate these policy components separately.

It is worth reiterating here the potential for the EITC to generate both marriage subsidies and penalties. Many of these differences depend on where individuals reside on EITC benefit schedule and the number of children included in the tax unit. Unfortunately, it is not possible using aggregate Vital Statistics data to tease out differential EITC effects across families with different observable characteristics. I merely point out these potentially offsetting effects as another explanation for why the EITC does not appear to be correlated with aggregate divorce flows.

It should be noted, however, that the advance payment option does not fully warrant a change in the EITC lag structure. An analysis by the U.S. General Accounting Office (1992) finds that few potential claimants are aware of this option, and only 0.5% of EITC recipients chose to obtain their benefits via this method.

Another solution is to use Vital Statistics Detailed Data, which provide counts of marriages and divorces by state of residence, along with a number of basic demographic characteristics. However, the Detailed Data contain a number of serious flaws. First, due to budget constraints and concerns about quality, data collection was discontinued in 1995. When the system was in place, only 41 states and the District of Columbia participated in marriage data collection and 31 states and the District of Columbia participated in the divorce data collection. Only 77% of marriages and 49% of divorces were captured by the Detailed Data. Furthermore, perhaps the most important demographic variable for the purposes of the EITC, educational attainment, has not been collected since 1989.

The CTC is a dummy variable that equals unity in the years after its implementation. The EGTRRA is a dummy variable that equals unity for all state-year combinations after 2001. Family caps are measured by a dummy that equals unity in the state-years after its implementation. The CCDF variable is the combined federal and state expenditures per child ages 0–12.

A final specification check should be mentioned. Using unbalanced panel data reduces the magnitude of the EITC coefficient in the marriage model, rendering it imprecisely estimated (βnew marriage = −0.035; SE = 0.026 and βnew divorce = 0.006; SE = 0.028). However, estimating level measures of the dependent variable on the unbalanced panel leads to a statistically significant effect of the EITC on new marriages (βnew marriage = −0.003; SE = 0.001 and βnew divorce = 0.0003; SE = 0.0004). In neither case is the EITC coefficient significant in the new divorce model.

The negative border state coefficients could be an artifact of unobserved regional factors that influence EITC policymaking and marriage norms. To investigate this possibility, I add region dummies to all models in Table 6. Doing so does not alter the sign, magnitude, or significance of the coefficients on the border state dummy and EITC maximum credit.

EITC noncompliance has been a topic of substantial interest. A study of the 1994 tax year found that over 20% of EITC payments were made erroneously, most of them in overclaims, and one-third of these overclaims were due to misreporting of filing status by married partners (McCubbin 2000; Scholz 1994, 1997). Moreover, a recent analysis of 1999 tax returns found that between $8.5 and $9.9 billion of EITC payments (or 27.0 to 31.7%) were paid in error (U.S. Department of the Treasury 2002). Although the report cited qualifying child requirements as the most important factor behind the erroneous payments, married taxpayers filing as single (or head of household) was another key factor.

References

Acs, G., & Maag, E. (2005). Irreconcilable differences? The conflict between marriage promotion initiatives for cohabitating couples with children and marriage penalties in the tax and transfer systems. Policy Brief No. B-66. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Alm, J., & Whittington, L. (1995). Income taxes and the marriage decision. Applied Economics, 27, 25–31.

Alm, J., & Whittington, L. (1997). Income taxes and the timing of marital decisions. Journal of Public Economics, 64, 219–240.

Baughman, R., & Dickert-Conlin, S. (2009). The earned income tax credit and fertility. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 537–563.

Becker, G. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Bennett, N., Bloom, D., & Miller, C. (1995). The influence of nonmarital childbearing on the formation of first marriages. Demography, 32, 47–62.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (2000). Unnatural experiments? Estimating the incidence of endogenous policies. The Economic Journal, 110, F672–F694.

Bitler, M., Gelbach, J., Hoynes, H., & Zavodny, M. (2004). The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography, 41, 213–236.

Blackwell, D., & Lichter, D. (2000). Mate selection among married and cohabiting couples. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 275–302.

Blank, R. (1999). Analyzing the length of welfare spells. Journal of Public Economics, 39, 245–274.

Blank, R. (2002). Evaluating welfare reform in the U.S. Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 1105–1166.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., & Waldfogel, J. (2000). Understanding young women’s marriage decisions: The role of labor and marriage market conditions. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 53, 624–647.

Brien, M. J. (1997). Racial differences in marriage and the role of marriage markets. Journal of Human Resources, 32, 741–778.

Cherlin, A. (1977). The effect of children on marital dissolution. Demography, 14, 265–272.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Attitudes, values, and entrance into cohabitational versus marital unions. Social Forces, 74, 609–634.

Congressional Budget Office. (1997). For better or for worse: Marriage and the federal income tax. http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=7&sequence=o.

Crouse, G. (1999). State implementation of major changes to welfare policies 1992-1998. Retrieved September 1, 2006, from http://aspe.hhs.gov/HSP/WaiverPolicies99/policy_CEA.htm.

Dickert-Conlin, S. (1999). Taxes and transfers: Their effect on the decision to end a marriage. Journal of Public Economics, 73, 217–240.

Dickert-Conlin, S., & Houser, S. (1998). Taxes and transfers: A new look at the marriage penalty. National Tax Journal, 51, 175–218.

Dickert-Conlin, S., & Houser, S. (1999). EITC, AFDC, and the female headship decision. Discussion paper no. 1192-99. Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin.

Dickert-Conlin, S., & Houser, S. (2002). EITC and marriage. National Tax Journal, LV, 25–40.

Duchovny, N. (2001). The Earned Income Tax Credit and fertility. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Maryland, Department of Economics.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. (2004). Taxes and labor market participation of married couples: The Earned Income Tax Credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1931–1958.

Ellwood, D. (2000). The impact of the earned income tax credit and social policy reforms on work, marriage, and living arrangements. National Tax Journal, 53, 1063–1105.

Ellwood, D., & Jencks, C. (2001). The growing differences in family structure: What do we know? Where do we look for answers? Working paper. Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Fang, H., & Keane, M. (2004). Assessing the impact of welfare reform on single mothers. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 1–116.

Fitzgerald, J. M., & Ribar, D. (2004). Welfare reform and female headship. Demography, 41, 189–212.

Friedberg, L. (1998). Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 88, 608–627.

Gittleman, M. (2001). Declining caseloads: What do the dynamics of welfare participation reveal? Industrial Relations, 40, 537–570.

Goldstein, J. (1999). The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography, 36, 409–414.

Gray, V. (1973). Innovation in the states: A diffusion study. American Political Science Review, 67, 1174–1185.

Grogger, J. (2003). The effects of time limits, the EITC, and other policy changes on welfare use, work, and income among female-headed families. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 394–408.

Hoffman, S. (2003). The EITC marriage tax and EITC reform. Working paper no. 2003-01. University of Delaware, Department of Economics.

Holtzblatt, J., & Rebelein, R. (2000). Measuring the effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on marriage penalties and bonuses. National Tax Journal, 53, 1107–1134.

Horvath-Rose, A., & Peters, H. E. (2001). Welfare waivers and non-marital childbearing. In G. Duncan & L. Chase-Lansdale (Eds.), Welfare reform: For better, for worse. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hoynes, H. (1997). Does welfare play any role in female headship decisions? Journal of Public Economics, 65, 89–117.

Joyce, J., Pearce, W., I. I. I., & Rosenbloom, J. (2001). The effects of child-bearing on women’s marital status: Using twin births as a natural experiment. Economics Letters, 70, 133–138.

Kaushal, N., & Kaestner, R. (2001). From welfare to work: Has welfare reform worked? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20, 699–719.

Lichter, D. T., Anderson, R., & Wayward, M. (1995). Marriage markets and marital choice. Journal of Family Issues, 16, 412–431.

Lichter, D. T., McLaughlin, D. K., & Ribar, D. C. (2002). Economic restructuring and the retreat from marriage. Social Science Research, 31, 230–256.

Looney, A. (2005). The effects of welfare reform and related policies on single mothers’ welfare use and employment in the 1990s. Working paper 2005-45. Finance and economics discussion series. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board.

McCubbin, J. (2000). EITC noncompliance: The determinants of misreporting of children. National Tax Journal, 53, 1135–1164.

Meyer, B., & Rosenbaum, D. (2001). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1063–1114.

Moffitt, R. (1994). Welfare effects on female headship with area effects. Journal of Human Resources, 29, 621–636.

Moffitt, R. (1998). The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In R. Moffitt (Ed.), Welfare, the family, and reproductive behavior. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Moffitt, R., & Rendall, M. (1995). Cohort trends in the lifetime distribution of female family headship in the United States. Demography, 32, 407–424.

Mooney, C., & Lee, M. (1995). Legislative morality in the American states: The case of pre-Roe abortion regulation reform. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 599–627.

Nagle, A., & Johnson, N. (2006). A hand up: How state Earned Income Tax Credits help working families escape poverty in 2006. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Qian, Z., Lichter, D., & Mellott, L. (2005). Out-of-wedlock childbearing, marital prospects, and mate selection. Social Forces, 84, 473–491.

Ressler, R. A., & Waters, M. S. (2000). Female earnings and the divorce rate: A Simultaneous equations model. Applied Economics, 32, 1889–1898.

Rosenbaum, D. (2000). Taxes, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and marriage. Working paper. University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Department of Economics.

Schoeni, R., & Blank, R. (2000). What has welfare reform accomplished? Impacts on welfare participation, employment, income, poverty, and family structure. Working paper no. 7627. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Scholz, J. K. (1994). The Earned Income Tax Credit: Participation, compliance, and anti-poverty effectiveness. National Tax Journal, 47, 63–87.

Scholz, J. K. (1997). Deputy assistant secretary for tax analysis, U.S. Department of the Treasury. Testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means. Washington, DC, May, 1997.

Shipan, C., & Volden, C. (2008). The mechanisms of policy diffusion. American Journal of Political Science, 52, 840–857.

Steele, F., Kallis, C., Goldstein, H., & Joshi, H. (2005). The relationship between childbearing and transitions from marriage and cohabitation in Britain. Demography, 42, 647–673.

Thorton, A., & Rodgers, W. (1987). The influence of individual and historical time on marital dissolution. Demography, 24, 1–22.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2004). Number, timing and duration of marriages and divorces, 2004. http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/marr-div/2004detailed_tables.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS). (1997). Setting the baseline: A report on state welfare waivers. Retrieved September 1, 2006, from http://aspe.hhs.gov/HSP/isp/waiver2/title.htm.

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service. (2002). Compliance estimates for Earned Income Tax Credit claimed on 1999 returns. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/compesteitc99.pdf.

U.S. General Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). (1997). Welfare reform: States’ early experiences with benefit termination. Report No. HEHS-97-74. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accountability Office.

U.S. General Accounting Office (U.S. GAO). (1992). Earned Income Tax Credit: Advance payment option is not widely known or understood by the public. GAO/GGD-92-26. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office.

U.S. General Accounting Office (U.S. GAO). (1996). Income tax treatment of married and single individuals. Report No. GAO/GGD-96-175. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means (2004). Green book, background on material and data on programs within the jurisdiction of the committee on ways and means. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Whittington, L. (1992). Taxes and the family: The impact of the tax exemption for dependents on marital fertility. Demography, 29, 215–226.

Whittington, L., & Alm, J. (1997). Till death or taxes do us part: The effect of income taxation on divorce. Journal of Human Resources, 32, 388–412.

Whittington, L., Alm, J., & Peters, E. (1990). Fertility and the personal exemption: Implicit pronatalist policy in the United States. American Economic Review, 80, 545–556.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96, 1802–1820.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herbst, C.M. The Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Marriage and Divorce: Evidence from Flow Data. Popul Res Policy Rev 30, 101–128 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-010-9180-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-010-9180-3