Abstract

Since the advent of public opinion polling, scholars have extensively documented the relationship between survey response and interviewer characteristics, including race, ethnicity, and gender. This paper extends this literature to the domain of language-of-interview, with a focus on Latino political opinion. We ascertain whether, and to what degree, Latinos’ reported political attitudes vary by the language they interview in. Using several political surveys, including the 1989–1990 Latino National Political Survey and the 2006 Latino National Survey, we unearth two key patterns. First, language-of-interview produces substantively important differences of opinion between English and Spanish interviewees. This pattern is not isolated to attitudes that directly or indirectly involve Latinos (e.g., immigration policy, language policy). Indeed, it emerges even in the reporting of political facts. Second, the association between Latino opinion and language-of-interview persists even after statistically controlling for, among other things, individual differences in education, national origin, citizenship status, and generational status. Together, these results suggest that a fuller understanding of the contours of Latino public opinion can benefit by acknowledging the influence of language-of-interview.

Similar content being viewed by others

At least since the 1940s, survey researchers have observed that interviewer characteristics can profoundly shape the answers respondents report (Katz 1942; Hyman et al. 1954). Consider the influence of race-of-interviewer (Hyman et al. 1954; Schuman and Converse 1971; Hatchett and Schuman 1975–1976; Schaeffer 1980; Campbell 1981; Cotter et al.1982; Anderson et al. 1988a, b; Finkel et al. 1991; Davis 1997a, b). African Americans who are interviewed by Whites often report substantively distinct responses on some questions than their counterparts who are interviewed by another African American. The same is true of White Americans. And, there is evidence of parallel patterns with interviewer ethnicity (Weeks and Moore 1981; Reese et al. 1986; Hurtado 1994) and interviewer gender (Johnson and DeLamater 1976; Groves and Fultz 1985; Kane and Macaulay 1993). These findings, moreover, are not limited to face-to-face interviews. They also emerge in telephone surveys (Cotter et al. 1982), even when all interviewers share the same phenotypic race (Sanders 1995).

While the variation between survey response and interviewer characteristics was initially viewed as a methodological artifact or threat to internal validity, scholars now explain it as an indicator of broader social and political phenomena (Kane and Macaulay 1993; Sanders 1995; 2003; Davis 1997a). Davis (1997b) argues quite persuasively that the influence of race-of-interviewer throws significant light on the nature of racial interactions. In Sanders’s work on perceptions of interviewers’ race, the exchange of words—accent, inflection, dialect, even enunciative mannerisms—affects how “race” is ascribed in phone interviews. She also reminds us that survey interviews are conversations that can be private or public, racially segregated or integrated: choices which bear on the prospects of deliberative and multiracial democracy.

In this paper, we examine a relatively unexplored aspect of survey interviews, namely, the degree to which language-of-interview is associated with political opinions (e.g., Welch et al. 1973; Pérez 2009). Specifically, we examine English/Spanish surveys of Latino political attitudes. Given the growth of the U.S. Latino population, public opinion researchers have increasingly deployed bilingual surveys to better understand the political opinions of this ethnic group (e.g., Abrajano 2010; Abrajano and Alvarez 2010; Sanchez 2006; Michelson 2003). These surveys are often rigorously translated to optimize their equivalence across English and Spanish.Footnote 1 Thus, the working assumption in applied analyses of Latino political attitudes is that language-of-interview has no systematic influence on the shape of Latino opinion. We revisit this working assumption and find that individual differences in language-of-interview are regularly associated with individual differences in Latino political attitudes. This pattern is not temporally bound, as it emerges in older and more recent surveys of Latino opinion. Moreover, language-of-interview differences are not isolated to questions pertaining to language policy, immigration, or issues that (in)directly refer to Latinos. Indeed, we detect them even in the reporting of political facts. Most importantly, the link between interview language and Latino opinion remains after we statistically control for individual differences in demographics, language ability, and the social dynamics of survey interviews. We conclude that language-of-interview is a critical, yet under-studied influence on the shape of Latino opinion.

The Relationship Between Language-of-Interview and Latino Political Attitudes

In studying the connection between language-of-interview and Latino opinion, we do not mean to imply we are the first to study the role of language in polling. A trove of scholarship finds that language affects the development and administration of surveys (e.g., Brislin 1970; Jacobson et al. 1960; Ervin and Bower 1952–1953). Yet this literature overwhelmingly centers on the challenges and implications of translated questionnaires, with a strong focus on non-U.S. contexts (e.g., Elkins and Sides 2010; Davidov 2009; Chan et al. 2007; Byrne and Campbell 1999; but see Welch et al. 1973). In contrast, we examine the link between language-of-interview and differences in opinion among Latinos, America’s largest racial/ethnic minority. In this way, we contribute to fledgling research on language and the nature and quality of survey data on this key segment of the U.S. population (Lee et al. 2008; Pérez 2009; Garcia 2010).

We focus strictly on the possible influence of language-of-interview on Latino political attitudes. That is, we are interested in the degree to which individual differences in language-of-interview correspond with individual differences in Latinos’ political opinions. We readily admit that the choice of interview language is substantively important in its own right, similar to the decision to participate (or not) in opinion polls (e.g., Berinsky 2004; Keeter et al. 2000, 2006; Groves 2006).Footnote 2 Yet the choice of interview language is a question better answered through alternate research designs with greater leverage over the psychological mechanisms animating this choice (e.g., survey-experiments) (Pérez 2011, p. 448). Our study therefore focuses on attitudinal differences between Latino survey respondents who interview in English or Spanish. In this way, our analysis is akin to modal survey analyses of public opinion, which center on attitudinal differences between survey respondents, rather than differences between survey respondents and non-respondents (e.g., Curtin et al. 2000; Keeter et al. 2000).

Of course, some bias can still potentially affect an analysis like ours. Specifically, Sullivan et al. (1979) observe that survey responses can display bias not only due to non-response, but also because some people are less able or willing to articulate coherent political ideas and beliefs. For our part, our tests of the relationship between interview language and Latino opinion will account for some of the likely correlates of this individual difference (e.g., education, income, age), thereby lessening the possible impact of this form of bias.

Against this backdrop, we start from two premises. First, language can leave a lasting imprint on one’s political and social views. As political and social psychologists have shown, language sometimes colors people’s interpretation of survey items (Pérez 2011), as well as the memories, ideas, and beliefs they develop and store in memory (Marian and Neisser 2000). Second, the influence of language over people’s political and social views can vary across distinct languages, as illustrated by research on the challenges of measuring public opinion in cross-national settings (Jacobson et al. 1960). These two premises are playfully captured by the writer Vladimir Nabokov, who, when asked to name the language he considered most beautiful, replied that “my head says English, my heart, Russian, and my ear, French.”

We begin our inquiry by demonstrating a prima facie case of opinion variance by interview language. Our data are from the 1989–1990 Latino National Political Survey (LNPS).Footnote 3 We center on the LNPS because it is a seminal dataset on Latino opinion, though, as we will show, the patterns we unearth here emerge in more recent datasets. The LNPS completed 2,817 face-to-face interviews with Latinos between July 1989 and April 1990. 1,546 respondents were Mexican, 589 Puerto Rican, and 682 Cuban. Roughly 60 % of respondents chose Spanish as their preferred language-of-interview.Footnote 4 The linguistic distribution of interviews by ethnicity is as follows: about 50 % of Mexican interviews, roughly 60 % of Puerto Rican interviews, and more than 80 % of Cuban interviews were conducted in Spanish.Footnote 5

Table 1 shows the distribution of responses to 44 LNPS items for which a reliable language-of-interview difference is detected. The items fall under four rubrics: (1) questions about core political values and policy preferences (Table 1A); (2) questions about policy preferences affecting Latinos (e.g., language policy, immigration; Table 1B); (3) feeling thermometer ratings of Latino home countries, Latino subgroups, and other U.S. groups (Table 1C); and (4) perceptions of discrimination against Latino and non-Latino groups in the U.S. (Table 1D). The English/Spanish wording for these items is located in Table A (online appendix).

The sheer number and variety of items in Table 1 for which there is a reliable language-of-interview gap is remarkable.Footnote 6 Much like Hatchett and Schuman’s (1975–1976) findings on race-of-interviewer differences in opinion reports, these language gaps are not isolated to language-related, Latino-related, or even race and ethnicity-related items, broadly construed. In table 1A, English interviewees appear much less willing to abide by inequalities in life chances and much more patriotic toward the U.S. Spanish interviewees appear much more trusting of government officials and more supportive of an active government role in solving problems affecting the nation, localities, and the respondent’s ethnic group. On policy items, Spanish interviewees are generally more supportive of greater government spending across several domains. Finally, sizeable language-of-interview differences emerge for broad social issues. Spanish interviewees are less supportive of a woman’s right to choose and the death penalty. Collectively, these gaps range from a modest 5 % (on support for increased spending on Blacks) to more than 20 % (on support for unequal life chances).

Table 1B shows similarly substantive differences across a wide spectrum of questions about language and education policy and home country politics. English interviewees are more supportive of monolingual and monocultural policies than Spanish interviewees. With immigration policy, English interviewees register greater opposition to giving special preferences to Latino immigrants. Finally, English interviewees are almost twice as likely as Spanish interviewees to be concerned with U.S. politics than home country politics, and there are distinct differences in opinion over Central America by interview language.

Table 1C extends these language-of-interview gaps to affect toward social groups. For instance, Spanish interviewees respond more warmly to Latino home countries and groups. The exception here is that Spanish interviewees are colder toward Mexican Americans (but warmer toward Mexico and Mexican immigrants). Spanish interviewees also reacted more coldly than English interviewees to other U.S. racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Blacks, Whites, and Jews).

The most striking variations by interview language arise in perceptions of discrimination against different U.S. groups. Table 1D reveals one principal relationship: Spanish interviewees are overwhelmingly more likely to view all groups as facing little discrimination. This pattern arises for all groups identified—e.g., Blacks, Jews, and women—and ranges between 22 and 35 %. Thus, while Spanish interviewees appear warmer toward Latino groups, this does not translate into stronger perceptions of discrimination against Latinos, in particular.

Language-of-Interview Differences as Omitted Variable Bias

Once survey items are translated, it is generally presumed they are functionally equivalent across languages, including English and Spanish (Jacobson et al. 1960; Brislin 1970; Pérez 2009). For analyses of Latino opinion, this implies a plausible null hypothesis: language-of-interview should be unrelated to Latinos’ attitudes. Yet our preliminary evidence so far suggests a rejection of this null hypothesis. To bolster our case, we consider three alternative explanations of the relationship between language-of-interview and Latino opinion.

We first consider whether opinion differences by language-of-interview are due to omitted variable bias (Gujarati 2003). Since we have looked only at whether Latino opinion varies by interview language and nothing else, it is plausible the opinion gaps we observe arise from other individual differences that are related to, but distinct from, the language-of-interview, including age, education, and income.Footnote 7 To test whether the association between interview language and Latino opinion persists in a multivariate framework, we regress each of our 44 items on language-of-interview, where 1 = English and 0 = Spanish. We then add to these models statistical controls for Latino differences in age, education, income, employment status, homeownership status, gender, marital status, and self-reported race. When we do this, we find a reliable language-of-interview gap for 40 of 44 items.Footnote 8

One may object, however, that performing this kind of global statistical analysis over 44 dependent variables obliterates important nuances, such as which additional covariates matter and how substantive are the language-of-interview differences that remain in the presence of these additional covariates. To put a finer point on this broad pattern, Tables 2 through 4 focus on three items: (1) opposition to unequal life chances; (2) concern for the politics of one’s ethnic “home” (i.e., Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico), and (3) perceptions of discrimination facing Puerto Ricans in the U.S. Other choices might have been made, but these three items illustrate language-of-interview differences on a question of core values (i.e., not related to ethnicity), on a question related to one’s ethnic “home,” and on a question about the experiences of a specific Latino group in the U.S.Footnote 9 For each of these three items, the first column in Tables 2, 3, and 4 represents the bi-variate association, regressing each dependent variable on language-of-interview. The second column, labeled “Omitted Vars. Bias (1),” controls for respondents’ age, education, family income, home ownership, employment status, sex, race, and marital status.

Two salient findings emerge in Tables 2, 3, and 4. First, the number of additional covariates that matters varies across questions. For unequal life chances and concern for ethnic home politics, only two of the covariates are statistically significant. In turn, for perceived anti-Puerto Rican discrimination, most of the additional covariates seem to matter. Second, while the gaps in language-of-interview diminish, they remain statistically reliable across all three questions.

To be more precise about how much language-of-interview differences change as we control for these additional demographic factors, the magnitudes of these gaps are estimated for select categories in Table 5.Footnote 10 In the bi-variate case, English interviewees are 12 % more likely than Spanish interviewees to oppose unequal life chances, and 37.7 % more likely to focus on U.S. rather than ethnic home politics. In turn, Spanish interviewees are 23.6 % more likely to think Puerto Ricans face little discrimination.Footnote 11 Once individual demographic differences are held constant, these language-of-interview gaps decline to 7.1 % (opposition to unequal life chances); 37.6 % (concern for U.S. rather than ethnic home politics); and 18.3 % (perception that Puerto Ricans face little discrimination), respectively.

Of course, one might reasonably object that the choice of these demographic variables is rigged to favor the persistence of opinion gaps by interview language. Since language-of-interview is likely related to one’s level of acculturation and ethnicity, these initial controls may simply focus on the wrong set of demographic attributes. Here the role of acculturation is especially relevant, since many Latinos have immigrant origins. Acculturation refers to the degree to which people learn and adapt to a host society’s culture and norms (e.g., Marín and Marín 1991; Alba and Nee 2003), with greater levels of acculturation often shaping the direction and intensity of individuals’ attitudes and behavior (Branton 2007). Acculturation, however, is not confined to a single domain. Thus, scholars often gauge it in terms of immigrant generation, time spent in the U.S., citizenship status, and English language familiarity, with generational status often receiving special emphasis.

Bracketing the role of language ability for the moment (we return to it immediately below), the LNPS allows us to test for the influence of acculturation and ethnicity through the following covariates: immigrant generation, the age at which one immigrated, citizenship status, immigrant status, and ethnicity—Cuban, Puerto Rican, or Mexican. This richer set of demographic controls fares better in explaining some of the variation by interview language. For instance, in terms of acculturation, immigrant generation is generally unrelated to each outcome, while citizenship status is often related to them. In terms of ethnicity, being Cuban or Puerto Rican is reliably associated with most of the dependent variables under study. But even after accounting for this richer battery of covariates, reliable language-of-interview differences persist.

Looking closely at this new set of covariates in Tables 2, 3, and 4 (under “Omitted Vars. Bias (2)”), we find little value added for opposition to unequal life chances, but substantial influence on concern for ethnic “home” politics and perceptions of anti-Puerto Rican discrimination. Table 5 shows that controlling for various aspects of one’s immigrant and ethnic background, English interviewees are now 8.3 % more likely to oppose unequal life chances. In turn, the first difference between English and Spanish interviewees in concern for U.S. politics is now 22.9 %, while for perceptions of anti-Puerto Rican discrimination, it is 7.2 %.Footnote 12

Language-of-Interview Differences as Measurement Error

So far, we have cast doubt on the possibility that demographic and social differences between Latinos completely explain the association between interview language and Latino opinion. Another explanation to consider is whether respondents vary by language-of-interview due to language familiarity. In our prior discussion of acculturation, we noted that English language familiarity is one way scholars operationalize this concept. Yet the degree of English language familiarity could also cloud a person’s “true” opinion. Specifically, Latinos interviewed exclusively in English might make more mistakes in interpreting a question if their knowledge of English is limited; they seldom use the English they know; or their ability to move between languages is encumbered. The view here is that language-of-interview is a source of measurement error and that a person’s choice of interview is a proxy for her language ability.

By this measurement error explanation, we should find significant differences in opinion between respondents in monolingual surveys and their counterparts in bilingual polls. Yet a comparison of responses to like items in the monolingual American National Election Studies (ANES) and the bilingual LNPS suggests ANES Latinos are comparable to LNPS English interviewees, yet different from LNPS Spanish interviewees.Footnote 13 And, among LNPS respondents, we have already observed response differences by language-of-interview (see Table 1).

Furthermore, language-of-interview differences in opinion persist even if we disaggregate LNPS respondents by language familiarity. Using two LNPS measures of language familiarity—self-professed ability and language usage at home—we created three groups: (1) Spanish primary respondents; (2) bilingual respondents, and (3) English primary respondents. We find language-of-interview differences for 38 out of our 44 items among Spanish primary respondents and 39 items for bilingual respondents. A drop-off occurs among English primary respondents, where significant language-of-interview gaps remain in only 10 items. This result largely arises from sample size differences. By our coding of language familiarity, there are 1,061 Spanish primary respondents, 1,369 bilingual respondents, and only 216 English primary respondents.Footnote 14

An alternate reading of the measurement error hypothesis is that interviews in a second language yield systematically biased interpretations of survey items (e.g., Jacobson et al. 1960; Pérez 2009). Questions involving abstractions, “thick” concepts, or ideas that travel poorly between languages may skew responses in a specific direction. We can test this version of the measurement error hypothesis by conducting a close textual reading of a survey instrument; generating expectations about which questions are likely to yield biased interpretations; and then see if the data bear out these expectations. Ab initio, our comparison of English and Spanish items in the LNPS (Table A, online appendix) identifies some idiosyncratic differences.Footnote 15 For instance, the Spanish question on abortion directs respondents to think about their opinion within the last few years, a prompt that is not given in the English version. Also, the Spanish item on the death penalty uses the stronger word “assassinate”, while the English version uses “murder.” Nevertheless, this close textual comparison of English and Spanish items does not generate explanations across all 44 items for which we find reliable language-of-interview differences. This is unsurprising when we recall that bilingual survey instruments like the LNPS have already been rigorously translated to optimize the equivalence of English/Spanish survey items (Jacobson et al. 1960; Brislin 1970; Pérez 2009).Footnote 16

A more expedient strategy is to proceed as we have been doing by testing for the independent association between one’s opinion and one’s language-of-interview choice, while statistically controlling for the influence of individual differences in language familiarity. Again, if the measurement error hypothesis is correct, the language-of-interview differences we have uncovered should vanish. The three controls available for use in the LNPS are respondents’ self-rated fluency in English, their primary language at home, and their bilingualism (measured as respondents’ ability to translate a number of sentences from Spanish to English).

Tables 2, 3, and 4 reveal that the addition of language use and ability as covariates barely changes the association between language-of-interview and opposition to unequal life chances. For concern about home country politics and perceived discrimination against Puerto Ricans, the inclusion of these covariates reduces—but does not eliminate—the relationship between interview language and Latino opinion. Indeed, Table 5 shows English interviewees are still 9 % more likely to oppose unequal life chances and 18 % more likely to privilege U.S. politics; while Spanish interviewees are 6 % more likely to view Puerto Ricans as facing little discrimination. Clearly, language proficiency and use are a key part of the story behind language-of-interview gaps in Latino opinion. But they are not the whole of this story.

Language-of-Interview Differences as Social Desirability

Beyond omitted variable bias and measurement error, survey responses may also vary by interview language because the particular social dynamic that unfolds during an interview differs between languages. A discussion between two parties in English may be meaningfully distinct compared to a parallel discussion in Spanish (over identical topics, with the same structural relationship between conversation partners). The prevailing explanation of opinion variance by interviewer characteristics is premised on this view. By this social desirability hypothesis, respondents may try to anticipate what an interviewer wants to hear rather than report their true attitude. The motivation here is to avoid offending an interviewer by being agreeable. This dynamic is especially likely where an interviewer and respondent diverge (converge) on a characteristic with discernible and commonly understood social divisions and status differentials.

Race, ethnicity, and gender are such characteristics in U.S. society today. For instance, Whites express more willingness to vote for a Black candidate in the presence of a Black rather than White interviewer (Finkel et al. 1991). People are even apt to give socially desirable responses on their self-reported voting behavior, which may influence their actual voting behavior (Anderson et al. 1988a). In such instances, respondents acquiesce or defer when a status differential is perceived between oneself and an interviewer (Campbell 1981).

Language is a somewhat less obvious situation. In the case of interpersonal deference, it is insufficient for social dynamics to be an important aspect of survey interaction. Rather, the nature of interpersonal deference must be fundamentally different between a conversation held by two Spanish speakers and one held by two English speakers. An interviewer may judge differently the status and performance of a Latino respondent (e.g., vis-à-vis their level of competence and cooperation) if they are conversing with a respondent in English rather than Spanish. And, a respondent may view the status, motivation, and legitimacy of a Spanish-speaking interviewer differently from that of an English-speaking one. Thus, respondents may opt for the “politically correct” response on sensitive questions or, even absent any racial or linguistic coding, may simply acquiesce to the perceived preferences of the interviewer.

When considering an immigrant-based group like Latinos, there may be social divisions and perceived status differences based on English as the dominant U.S. tongue. Thus, the selection of interview language might hinge on a choice between assimilation into dominant cultural norms or the (re)affirmation of one’s ethnic culture. If this is the case, then the selection of interview language may not simply be a matter of flattening or heightening social status and deference, but also enabling or disabling different forms of ethnic expression.Footnote 17

For the present purposes, we are agnostic about this refinement of the social desirability hypothesis.Footnote 18 The key question is whether measures of such perceived status differences can explain the variation in Latino opinion by language-of-interview. The LNPS includes six potential indicators: respondents’ sense of control over their destinies; interviewer evaluations of respondents’ level of understanding and cooperativeness; interviewer assessments of respondents’ phenotype; and, as an indirect measure, the presence of a third party during the interview (we code for the presence and duration of the party). Presumably, higher levels of perceived self-control and higher interviewer ratings of respondent understanding and cooperativeness should weaken social desirability pressures. The influence of phenotype and third party presence, based on race-of-interviewer studies, is likely contingent on the interviewer’s phenotype and the particular relationship between the respondent and third party.

We enter these indicators as covariates to assess whether a reliable association between interview language and Latino opinion emerges. Tables 2, 3, and 4 illustrate how social desirability tempers the influence of language-of-interview. In the case of unequal life chances, interviewer assessments of respondent understanding and cooperativeness, and the presence and duration of a third party during the interview, are significantly related to survey response. In the case of attention to ethnic home politics and perceived anti-Puerto Rican discrimination, no significant relationships emerge. Table 5 displays the magnitudes of language-of-interview differences after controlling for social desirability and the previously examined covariates. The added influence of social desirability pressures is minimal. English interviewees are about 8 % more likely to oppose unequal life chances and 17 % more likely to be concerned with U.S. politics; while Spanish interviewees are nearly 5 % more likely to sense Puerto Ricans face little discrimination.Footnote 19

To be sure, a completely different variant of social desirability lurks in the heterogeneity that is present within languages. Single concepts in the same language are often denoted by different words, which can sometimes have varied connotations. For example, in Mexican Spanish the concept insect is typically known as insecto, while in other Spanish-speaking parts of the Americas, it is known as bicho. Yet in nations like Puerto Rico, bicho has a sexual connotation (i.e., a popular reference to a part of the male anatomy). Moreover, even in the absence of varied connotations, nuances in word choice still arise for basic concepts, including colors like red (e.g., rojo, colorado) and black (e.g., negro, prieto).

In survey settings, this state of affairs suggests items might display slippage across people from different national origin groups who share the same language. Yet datasets like ours do not typically differentiate between varied forms of Spanish or English (consider, e.g., English spoken in New England versus English spoken in the South). Indeed, in translating the items in our datasets, the principal investigators aimed to design items that optimized both their inter- and intra-language equivalence (e.g., de la Garza et al. 1998).

Our sense, however, is that if intra-language heterogeneity affects Latino opinion, it is more likely to yield differences in the intensity of attitudes, but not their direction. Consider three native Spanish speakers: a Puerto Rican, Mexican, and Cuban. Let us assume a Spanish survey item is worded in a way that privileges Puerto Rican Spanish. Here, the other Spanish speakers can still infer some meaning based on the item’s syntax. Thus, they will have some understanding of the item, just not as complete as their Puerto Rican counterpart’s (i.e., more measurement error). Hence, their collective responses will underestimate a given attitude. Viewed this way, our analysis likely yields conservative estimates of language-of-interview gaps, since surveys like ours typically fail to distinguish varieties of the same language.Footnote 20

Language-of-Interview Differences: Pervasive, Persistent, and Reproducible?

So far our analysis finds that language-of-interview can leave an imprint on the survey answers Latinos report. But, have we unearthed durable language differences in opinion because we focused on the 1989–1990 LNPS—a seminal, but also older survey of Latino political opinion? In this section, we underline the breadth of the association between language-of-interview and mass Latino opinion by documenting its presence in the 2006 Latino National Survey (LNS), a more recent but equally comprehensive survey of Latino political attitudes. This English/Spanish telephone survey ran from November 17, 2005 through August 4, 2006, and yielded 8,634 completed interviews of Latino residents in the U.S.Footnote 21 We use data for the five largest national origin groups in the survey: Cubans, Dominicans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Salvadorans (N = 7,688). This allows us to create several distinct groups with a large number of cases, thus ensuring enough statistical power to detect the influence of national origin on Latino opinion.Footnote 22

We investigate the relationship between language-of-interview and four constructs measured by 21 items.Footnote 23 These constructs are: (1) political knowledge; (2) Latino attachment; 93) Americanism; and (4) perceived intergroup competition.Footnote 24 This mix of reported attitudes allows us to show that opinion variance by language-of-interview is also present in a more recent survey like the LNS. They also allow us to show that language-of-interview influences the reporting of subjective attitudes as well as political facts. Finally, the items attending these constructs are robustly correlated. This allows us to create scales for each variable under analysis, thus ruling out random measurement error in our dependent variables as an explanation for any uncovered associations between language-of-interview and the attitudes we examine (Brown 2006).Footnote 25

We model each of the aforementioned attitudes as a function of language-of-interview, plus measures for the alternate explanations assessed in Tables 2, 3, and 4. The covariates in these regressions closely mirror, but do not exactly match those in the LNPS data. While we control for most of the variables assessing the “omitted variable bias” explanation (e.g., age, education, national origin, and generational status), we are in a weaker position to test the “social desirability” and “measurement error” explanations with more than a single item. We point out, however, that in the LNPS analysis, measures of social desirability and measurement error were the least consistent predictors of Latino attitudes. That being said, we test for the influence of social desirability with Skin color, an item tapping respondent’s self-reported phenotype.Footnote 26 The measurement error explanation is tested in two ways. The first is through Switch language, a dummy indicator capturing individuals who switched their interview language in the course of the survey, which we treat as a proxy for language familiarity.Footnote 27 The second, noted earlier, is by scaling our dependent variables (Brown 2006).

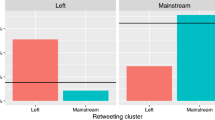

We begin by looking for preliminary evidence that differences by language-of-interview exist in these LNS items. Table C (online appendix) reports the gaps between English and Spanish interviewees on an item by item basis. Two main patterns emerge. First, differences by language-of-interview emerge in all items under investigation. And, in general, these differences range from small to substantively large. For instance, on the item Born in the U.S. in panel (iii), only 2 % more Spanish interviewees rate this item as very important compared to English interviewees. In contrast, in panel (i), 50 % of English interviewees correctly identified Republicans as more conservative than Democrats, while only 26 % of Spanish interviewees did so—a 24 % difference between both groups on this political knowledge item.

The basic pattern in Table C (online appendix) suggests attitudinal differences by interview language are also present in the 2006 LNS. The remaining question is whether these interview language gaps remain even after we control for the plausible influences of omitted variable bias, measurement error, and social desirability. To address this, we analyze the influence of language-of-interview on scales of (a) political knowledge, (b) Latino attachment, (c) Americanism, and (d) perceived intergroup competition. All variables in this analysis are recoded to vary from 0 to 1, which permits us to compare the relative magnitude of language-of-interview relative to other covariates in these models. For each of the dependent variables, higher values indicate greater levels of the relevant attitude. The results are displayed in Table 6.

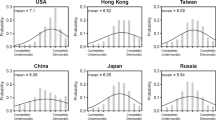

There we see the association between language-of-interview and each dependent variable persists despite a wide array of statistical controls. Moreover, the influence of language-of-interview is generally comparable to—and at times, larger than—the influence of other covariates, such as education, citizenship status, and national origin. For instance, all else constant, English interviewees report about 10 % more political knowledge than Spanish interviewees, which is comparable to the influence of being a citizen (.078) and Cuban (.160). Similarly, English interviewees report a level of attachment to Latinos that is, ceteris paribus, nearly 6 % less than Spanish interviewees; an influence which outperforms education (.026) and citizenship status (.021). Moreover, all else constant, English interviewees display a level of Americanism that is about 5 % lower than Spanish interviewees. Finally, English interviewees report a level of perceived competition with Blacks (relative to Latinos) that is nearly 4 % higher than Spanish interviewees; an influence comparable (in absolute terms) to one’s national origin (e.g., Puerto Rican = .038). Together, these results suggest the association between interview language and Latino political opinion is not limited to older Latino surveys, but rather, a phenomenon likely to emerge when Latinos are interviewed in more than one language.Footnote 28

Summary and Implications

This paper provides a glance into the power of language through the refracted lens of the survey interview. Our findings from the 1989–1990 LNPS and the 2006 LNS—two major datasets in the study of Latino political opinion—show that the relationship between Latino political attitudes and language-of-interview is pervasive and persistent. We examined a large and diverse number of opinion items and found reliable language-of-interview gaps in most of them. The language in which an interview is conducted can shape our understanding of respondents’ political beliefs, racial attitudes, and policy preferences. These language-of-interview differences partly reflect variation in respondent characteristics, language familiarity, and social desirability pressures. Yet they cannot be reduced to a technical matter about omitted variable bias, measurement error, or status deference in interpersonal settings.

Nevertheless, our analyses may be limited in two yet unconsidered ways. First, the explanations of language-of-interview differences we have examined are neither collectively exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. For one thing, words—their style and syntax—may be open to multiple, conflicting, and deeply subjective interpretations far beyond the explanations we have considered. The language-of-interview may impose an interpretive lens through which the entire survey interaction is defined, much like a framing experiment. If the proportion of Americans who support affirmative action can be so radically altered simply by changing the words we use to define affirmative action, then such interpretive differences across languages are almost sure to explain at least some of the variation by language-of-interview that we uncover.Footnote 29

Second, interview language differences may interact in significant ways with interviewers’ ethnicity. The psychodynamic elements of survey response—whether simple social desirability or Sanders’ interracial dialogue—are almost surely a combination of interview and respondent phenotype, mannerisms, language, etc. One limitation of our paper is that the LNPS and LNS do not include data about interviewer characteristics (e.g., race, ethnicity). Yet this does not threaten our conclusion that language-of-interview matters. The basic pattern we uncover can be reproduced using the 1999 Washington Post/Kaiser/Foundation/Harvard University Latino Survey, which asks respondents about the perceived ethnicity of their interviewer. The upshot is that the association between language-of-interview and Latino opinion remains even after we control for the ethnicity-of-interviewer.Footnote 30

Language-of-interview differences are unlikely limited to the LNPS, LNS, or to Latino mass opinion. Across several surveys, large proportions of immigrant-based populations like Latinos and Asian Americans opt for non-English interviews if offered a choice. Consider Asian Americans. In four ethnic-specific Los Angeles Times polls, 46 % of Filipino-Americans, 55 % of Chinese-Americans, 89 % of Vietnamese-Americans, and 90 % of Korean-Americans surveyed preferred to be interviewed in Tagalog, Cantonese or Mandarin, Vietnamese, and Korean, respectively. In the 2001 Pilot National Asian American Political Survey, the preferences are even more dramatic: 98 % of Vietnamese, 97 % of Chinese, and 87 % of Korean respondents chose to interview in a non-English language.Footnote 31 In each case, significant and durable differences in opinion by interview language emerge.Footnote 32

Moving forward, the persistence of opinion variance by language-of-interview suggests revisiting the broad guidelines for questionnaire translation. English/Spanish instruments are generally vetted against each other to identify and resolve discrepancies (Pérez 2009; see also Brislin 1970; Jacobson et al. 1960). Researchers typically go to great lengths to ensure these assessments are completed by qualified individuals who are, inter alia, bilingual, educated, and/or from certain Latino national origin groups (e.g., Mexican). Our results suggest investing additional effort in tightening the resemblance between those vetting bilingual questionnaires and those who might take the survey in either language. As Pérez (2009, p. 1532) explains, “[w]hether individual translators or focus groups are utilized to vet bilingual instruments, researchers are creating survey items based on the efforts of a few individuals. Here the risk is one of administering survey items that fail to capture concepts as understood by a general population.” In practical terms, our advice entails keeping the current approach to vetting bilingual questionnaires against each other, while placing stronger emphasis on making sure each language version of a questionnaire makes sense to an average respondent from the population one is sampling. Given real constraints in researchers’ time and resources, we view this more as an ideal for scholars to strive toward, rather than a tangible goal to be met in all cases.

Ultimately, our results direct greater attention to language-of-interview, a survey aspect often omitted from theoretical and empirical accounts of public opinion in multilingual samples. Yet by showing that interview language leaves an imprint on attitudinal reports, our paper serves, not as a warning or chiding, but as encouragement for further research into the origins and consequences of these language gaps. Indeed, by documenting a persistent association between Latino opinion and interview language, we provide—not a definitive account—but a key step in a longer scientific journey that examines the interface between language and surveys. We sincerely hope fellow scholars will oblige in this evolving collective endeavor.

Notes

For an overview of English/Spanish translations of political surveys, see Pérez (2009). We later return to this issue when we examine the links between item wording, measurement error, and opinion gaps by language-of-interview.

It is plausible the consequences of language-of-interview choice are similar to those that sometimes emerge when there are differences between survey respondents and non-respondents. In the latter case, individual differences in response/non-response can bias the results of opinion polls (Groves 2006). Yet research using survey-experimental designs finds that individual differences in response/non-response produce negligible amounts of bias in survey results (e.g., Curtin et al. 2000; Keeter et al. 2000, 2006). Determining whether something similar occurs in the realm of language-of-interview choice must await the development of comparable research designs.

Other bilingual surveys of Latinos (e.g., 1999 Washington Post survey of Latinos) find that closer to 40 % of respondents choose a Spanish interview. de la Garza et al. (1992) suggest their higher proportion of Spanish interviews may be due to an oversample of Puerto Ricans and Cubans in the LNPS. Other possibilities that de la Garza et al. do not discuss are the LNPS’s high response rate by today’s standards and its face-to-face mode, which may yield a higher proportion of Spanish interviews. A third possibility is that the underlying language use patterns of Latinos may have changed over time (i.e., more English-speaking Latinos in 1999 than in 1989).

Interviewer characteristics are unavailable in the LNPS, but de la Garza et al. (1998) note that 159 interviewers were trained, 138 interviewers conducted one or more interviews, and five-sixths of this pool was bilingual.

The actual sample used is N = 2,616 (645 Cubans, 1,428 Mexicans, and 543 Puerto Ricans).

LNPS Spanish interviewees are older, less educated and wealthy, less likely to own a home and to be employed, and more likely to be married. More than 90 % and less than 50 % of Spanish interviewees are foreign-born and citizens, respectively (Table B, online appendix). Per Sullivan et al. (1979), differences in age, education, income, and foreign-born and citizenship status are likely correlates of one’s ability to articulate political opinions, as well as language-of-interview. Our subsequent analyses include these individual differences as covariates. For more insight on Latino language pattern variation, see Lopez (1996), Portes and Schauffler (1996), and Stevens (1985, 1992).

The LNPS codes for six racial categories that do not map onto most survey race categories: White, black, other, Spanish label (e.g., Hispanic, Mestizo), Color oriented (e.g., Moron, Triune, Brown), and Race label (e.g., mulatto, North American). In Tables 2, 3, 4, we simply create a dummy variable for Whites (1 = Whites, 0 = all others).

Moreover, as we report later in the paper, the conclusions we draw from our analysis of these three items remain unchanged if we broaden our focus to other items in the LNPS, as well as items in other datasets (e.g., the LNS).

These values were calculated via Clarify (King et al. 2000), while holding other covariates at their means.

The unequal chances item (Table 1) combines respondents who “somewhat” and “strongly” disagree that unequal chances in life are all right.

The values in Table 5 reflect the magnitude of interview language differences, while additively controlling for each plausible account (e.g., demographic characteristics, language use and proficiency).

Results are based on a pooled ANES sample of Latinos from 1978 to 1998 (N = 1,438). LNPS respondents give fewer non-response answers, but this might arise from differences in survey mode (face-to-face vs. telephone interviews). When ANES items are compared to like items in a Latino telephone survey (e.g., the 1999 Washington Post poll or the 2002 Pew Hispanic Center poll), no differences in non-response emerge.

216 is the upper limit of cases on the items we examine, since a non-trivial number of observations are excluded due to ambivalent or non-compliant responses. There are several limitations with this kind of analysis, of course. One is that our measure of language familiarity could have significant measurement error, if substantial portions of our respondents coded “Spanish primary” or “English primary” in fact chose to be interviewed in a language other than the one they are most familiar with (23 % of Spanish primary respondents chose to interview in English, 47 % of English primary respondents chose to interview in Spanish). Second, language proficiency and usage may reflect distinct constructs. If we focus just on language proficiency, reliable gaps by interview language remain in 35 out of 44 items for Spanish primary respondents, 43 items for bilingual respondents, and only 5 items for English primary respondents (N = 483, 2,056, and 107, respectively).

When translating questionnaires, scholars strive to ensure similar meaning across languages (i.e., functional equivalence) (Pérez 2009). This often entails some sacrifice in strictly identical wording between items, since a one-to-one correspondence might fail to achieve uniform meaning (e.g., two languages may not have the same analog for a common concept). Critically, the LNPS and LNS appear to generally display functional equivalence. First, the second author in this paper is a native English and Spanish speaker. His examination of LNPS and LNS items detected a few idiosyncratic differences, which we note above in the text. Minor discrepancies like these are common when aiming for functional equivalence. Second, our conclusion about the uniform meaning of these translated items was further corroborated by an independent professional translator, who also failed to identify egregious translation differences that could undermine the goal of functional equivalence.

de la Garza et al. (1998) used a focus group approach to translate the English/Spanish items in the LNPS. Here the English instrument was designed by the Principal Investigators (PIs). The Spanish version was drafted by a Chilean Spanish speaker. The English questionnaire was then vetted against its Spanish analog by a focus group of six bilingual and college-educated individuals (2 Mexicans, 2 Puerto Ricans, 2 Cubans). Our analysis also uses the 2006 Latino National Survey (LNS) led by Fraga et al. Here the PIs prepared the survey in English and then translated it themselves into Spanish (several of the PIs are native or fluent Spanish speakers). This bilingual instrument was then evaluated by the study’s advisory board and graduate students, both of whom were native or fluent Spanish speakers. The PIs resolved any remaining discrepancies. The final instrument was field tested via a small pilot study. No further anomalies emerged (personal communication with LNS PI Michael Jones-Correa, October 24, 2012; personal communication with LNS PI John Garcia, October 29, 2012).

We can also rule out that language-of-interview gaps reflect other individual differences in respondent characteristics, rather than the interactive nature of the survey interview. This version of the social desirability thesis reduces to a variant of the “omitted variable bias” thesis, but we have already seen that language-of-interview gaps remain even after controlling for a large number of individual differences among Latino respondents.

The possibility of language-of-interview differences as a window into assimilation patterns and ethnic identity formation is a topic pursued more explicitly by Lee (2000).

In the interest of space, we have centered on these three items. Yet the link between interview language and Latino opinion broadly extends to other LNPS items. To show this, we used a random number generator to randomly select and report an additional eight (8) items, or 20 % of the remaining forty-one (41) in Table 1. A reliable association between language-of-interview and Latino opinion also emerges in six (6) of these eight (8) items, with five (5) of them achieving significance at the 5 % level and one (1) at the 10 % level. The coefficients/standard errors for these items are: (1) Love for U.S. (.23/.07); 2) Spending on science (−.21/.08); 3) Spending on the environment (.09/.09); 4) Cubans: Feel Therm. (−3.08/1.66); 5) Mexican Americans: Perc’vd Discrimination (.04/.07); 6) Asians-Perc’vd Discrimination (−.20/.07); 7) Teach U.S. history (.31/.08); and 8) Central American unrest (−.16/.08). All estimates are from ordered probit regressions, except those for item 4, which were yielded via OLS.

Intra-language heterogeneity is less of a problem when polling Latinos in subnational contexts where specific national origin group(s) predominate (e.g., Mexicans in Texas). Yet even in these cases, it still behooves scholars to pay greater attention to the resemblance between item translators and the population being sampled.

The mean interview was 40.6 minutes. The cooperation and response rates for this survey were 36.7 and 9.54 %, respectively (personal communication with LNS co-PI Gary Segura, March 2010).

The smallest national origin group in our analysis is Dominicans (n = 335). This group of cases still permits a meaningful analysis. The next smallest group excluded from our analysis is Guatemalans (n = 149). Here, if we were to include this group and find a reliable association, it would be hard to say whether it stems from being Guatemalan or something unique about these Guatemalans. Thus, we focus on the five groups described above.

The wording for these items can be found in Table A (online appendix).

In the interest of space, we define each construct here and refer readers to relevant scholarship. These citations are illustrative, but by no means exhaustive. Political knowledge refers to individuals’ factual information about politics (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996). Greater political knowledge, among other things, increases people’s engagement with politics. Latino attachment refers to identification with other Latinos. Formally, it refers to one’s identification with the social object, Latino (Turner et al. 1987). A key component of group attachment is a sense of commonality with it (Garcia 2003; Garcia Bedolla 2005). It is theorized the measures at hand capture this sense of attachment. Americanism refers to Latinos’ sense that national identity is ethno-racially delimited (e.g., Higham 1981; King 2000). Put differently, this construct captures the degree to which an individual sees the boundaries of national identity as ethno-racially impermeable. Thus, the more intense these perceptions, the less relevant American identity should be for one’s political behavior. On American identity and Latinos, see Fraga et al. (2010) and Citrin et al. (2007). On identity permeability, see Jackson et al. (1996) and Lalonde and Silverman (1994). Finally, perceived intergroup competition refers to one’s sense of conflict, across several domains, with an outgroup relative to one’s ingroup. Recently, this construct has been used to study Latino perceptions of political and economic competition with Blacks (Barreto et al. 2010, 2011; McClain et al. 2006, 2011). This construct is generally measured by subtracting one’s perceptions of competition with Latinos from one’s perceptions of competition with Blacks. We examine the items attending each set of perceptions.

See tables D through G (online appendix) for the relevant confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs).

In its raw metric, this item ranges from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating lighter phenotype.

Previous research finds this variable can, in some cases, affect Latinos’ survey response (Garcia 2010).

In fact, if we examine comparable items from the LNS and LNPS, this conclusion remains unchanged. While these two surveys do not share identical items, we did identify eight (8) LNS items that approximate those in the LNPS. Our tests uncover a reliable association between language-of-interview and Latino opinion for seven (7) out of eight (8) of these LNS items. See table H (online appendix) for the relevant items and statistical results.

Results are available from the authors upon request. In most instances, language-of-interview appears to be a more decisive influence on Latino mass opinion than does ethnicity-of-interviewer.

See Lee (2001).

References

Abrajano, M. A. (2010). Campaigning to a new electorate: Advertising to Latino voters. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Abrajano, M. A., & Alvarez, R. M. (2010). New faces, new voices: The Hispanic electorate in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Anderson, B. A., Silver, B. D., & Abramson, P. R. (1988a). The effects of race of the interviewer on measures of electoral participation by Blacks in SRC National Election Studies. Public Opinion Quarterly, 52(1), 53–83.

Anderson, B. A., Silver, B. D., & Abramson, P. R. (1988b). The effects of the race of the interviewer on race-related attitudes of Black respondents in SRC/CPS National Election Studies. Public Opinion Quarterly, 52(3), 289–324.

Barreto, M. A., Gonzalez, B., & Sanchez, G. (2010). Rainbow coalition in the Golden State? Exposing myths, uncovering new realities in Latino attitudes toward Blacks. In L. Pulido & J. Kun (Eds.), Black and brown Los Angeles: A contemporary reader. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Barreto, M. A., Sanchez, G., & Morin, J. (2011). Perceptions of competition between Latinos and Blacks: The development of a relative measure of inter-group competition. In E. Telles, G. Rivera-Salgado, & S. Zamora (Eds.), Just neighbors? Research on African American and Latino relations in the U.S.. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Berinsky, A. J. (2004). Silent voices: Opinion polls and political participation in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Branton, R. (2007). Latino attitudes toward various areas of public policy: The importance of acculturation. Political Research Quarterly, 60(2), 293–303.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press.

Byrne, M., & Campbell, T. L. (1999). Cross-cultural comparisons and the presumption of equivalent measurement and theoretical structure: A look beneath the surface. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(5), 555–574.

Campbell, B. (1981). Race-of-interviewer effects among southern adolescents. Public Opinion Quarterly, 45, 231–234.

Chan, B., Parker, G., Tully, L., & Eisenbruch, M. (2007). Cross-cultural validation of the DMI-10 measure of state depression: The development of a Chinese language version. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders, 195, 20–25.

Citrin, J., Lerman, A., Murakami, M., & Pearson, K. (2007). Testing Huntington: Is Hispanic immigration a threat to American identity? Perspectives on Politics, 5, 31–48.

Cotter, P. R., Cohen, J., & Coulter, P. (1982). Race-of-interviewer effects in telephone interviews. Public Opinion Quarterly, 46, 278–284.

Curtin, R., Presser, S., & Singer, E. (2000). The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 413–428.

Davidov, E. (2009). Measurement equivalence of nationalism and constructive patriotism in the ISSP: 34 countries in a comparative perspective. Political Analysis, 17(1), 64–82.

Davis, D. (1997a). Nonrandom measurement error and race of interviewer effects among African Americans. Public Opinion Quarterly, 61, 183–207.

Davis, D. (1997b). The direction of race of interviewer effects among African-Americans: Donning the Black mask. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 309–322.

de la Garza, R., DeSipio, L., Garcia, F. C., Garcia, J. A., & Falcon, A. (1992). Latino voices: Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban perspectives on American politics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Elkins, Z., & John, S. (2010). The Vodka is Potent, but the meat is rotten: Evaluating measurement equivalence across contexts. Unpublished manuscript, University of Texas at Austin.

de la Garza, R., Falcon, A., Garcia, F. C., & Garcia, J. A. (1998). Latino National Political Survey, 1989–1990. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university consortium for political and social research.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ervin, S., & Bower, R. T. (1952–1953). Translation problems in international surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16(4), 595–604.

Finkel, S. E., Guterbock, T. M., & Borg, M. J. (1991). Race-of-interviewer effects in a preelection poll. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55, 313–330.

Fraga, L. R., Garcia, J. A., Hero, R. E., Jones-Correa, M., Martinez-Ebers, V., & Segura, G. M. (2010). Latino lives in America: Making it home. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

John Garcia. A. (2003). Latino politics in America: Community, culture, and interests. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Garcia Bedolla, L. (2005). Fluid borders: Latino power, identity, and politics in Los Angeles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Garcia, F. C., Garcia, J., Falcon, A., & de la Garza, R. O. (1989). Studying Latino politics: The development of the Latino National Political Survey. PS, Political Science and Politics, 22(4), 848–852.

Garcia, J. A. (2010). Language-of-Interview: Exploring the effects of changing languages during the LNS interview. Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan.

Groves, R. M. (2006). Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70, 646–675.

Groves, R. M., & Fultz, N. H. (1985). Gender effects among telephone interviewers in a survey of economic attitudes. Sociological Methods and Research, 14, 31–52.

Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic econometrics. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Hatchett, S., & Schuman, H. (1975–1976). White respondents and race-of-interviewer effects. Public Opinion Quarterly, 39, 523–528.

Higham, J. (1981). Strangers in the land: Patterns of American nativism, 1860–1925. New York: Atheneum.

Hurtado, A. (1994). Does similarity breed respect? Interviewer evaluations of Mexican-descent respondents in a bilingual survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 58, 77–95.

Hyman, H., et al. (1954). Interviewing and social research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jackson, L. A., Sullivan, L. A., Harnish, R., & Hodge, C. N. (1996). Achieving positive social identity: Social mobility, social creativity, and permeability of group boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 241–254.

Jacobson, E., Kumata, H., & Gullahorn, J. E. (1960). Cross-cultural contributions to attitude research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 205–223.

Johnson, W. T., & DeLamater, J. D. (1976). Response effects in sex surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40, 165–181.

Kane, E. W., & Macaulay, L. J. (1993). Interviewer gender and gender attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 57, 1–28.

Katz, D. (1942). Do interviewers bias poll results? Public Opinion Quarterly, 6, 248–268.

Keeter, S., Kennedy, C., Dimock, M., Best, J., & Craighill, P. (2006). Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(5), 759–779.

Keeter, S., Miller, C., Kohut, A., Groves, R. M., & Press, S. (2000). Consequences of reducing nonresponse in a large national telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 125–148.

Kinder, D., & Sanders, L. M. (1990). Mimicking political debate with survey questions. Social Cognition, 8(1), 73–103.

King, D. (2000). Making Americans: Immigration, race, and the origins of the diverse democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 341–355.

Lalonde, R. N., & Silverman, R. A. (1994). Behavioral preferences in response to social injustice: The effects of group permeability and social identity salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 78–85.

Lee, T. (2000). Racial attitudes and the color line(s) at the close of the twentieth century. In P. M. Ong (Ed.), The state of Asian Pacific America, volume IV. Los Angeles: LEAP and UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

Lee, T. (2001). Language-of-interview effects and latino mass opinion. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Lee, S., Nguyen, H. A., Jawad, M., & Kurata, J. (2008). Linguistic minorities and nonresponse error. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 470–486.

Lien, P., Conway, M. M., Lee, T., & Wong, J. (2001). The pilot Asian American Political Survey: Summary report. In J. Lai & D. Nakanishi (Eds.), The National Asian Pacific American Political Almanac (pp. 2001–2002). Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

Lopez, D. E. (1996). Language: Diversity and assimilation. In R. Waldinger & M. Bozorgmehr (Eds.), Ethnic Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Marian, V., & Neisser, U. (2000). Language-dependent recall of autobiographical memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129(3), 361–368.

Marín, G., & VanOss Marín, B. (1991). Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

McClain, P. D., Carter, N. M., DeFrancesco Soto, V. M., Lyle, M. L., Grynaviski, J. D., Nunnally, S. C., et al. (2006). Racial distancing in a southern city: Latino immigrants views’ of Black Americans. The Journal of Politics, 68(3), 571–584.

McClain, P. D., Lackey, G. F., Pérez, E. O., Carter, N. M., Johnson Carew, J., Walton, E, Jr, et al. (2011). Intergroup relations in three southern cities: Black and White Americans’ and Latino immigrants’ attitudes. In E. Telles, G. Rivera-Salgado, & S. Zamora (Eds.), Just neighbors? Research on African Americans and Latino relations in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Michelson, M. R. (2003). The corrosive effect of acculturation: How Mexican Americans lose political trust. Social Science Quarterly, 84(4), 918–933.

Pérez, E. O. (2009). Lost in translation? Item validity in bilingual political surveys. The Journal of Politics, 71(4), 1530–1548.

Pérez, E. O. (2011). The origins and implications of language effects in multilingual surveys: A MIMIC approach with application to Latino political attitudes. Political Analysis, 19(4), 434–454.

Portes, A., & Schauffler, R. (1996). Language and the second generation: Bilingualism yesterday and today. In A. Portes (Ed.), The new second generation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reese, S. D., Danielson, W. A., Shoemaker, P. J., Chang, T., & Hsu, H. (1986). Ethnicity-of-interviewer effects among Mexican-Americans and Anglos. Public Opinion Quarterly, 50, 563–572.

Sanchez, G. R. (2006). The role of group consciousness in Latino public opinion. Political Research Quarterly, 59(3), 435–446.

Sanders, L. (1995). What is whiteness? Race of interviewer effects when all the interviewers are black. Paper presented at the American Politics Workshop, University of Chicago.

Sanders, L. (2003). Interracial opinion in a divided democracy, Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia.

Schaeffer, N. C. (1980). Evaluating race of interviewer effects in a national survey. Sociological Methods and Research, 8, 400–419.

Schuman, H., & Converse, J. M. (1971). The effects of Black and White interviewers on Black responses in 1968. Public Opinion Quarterly, 35, 44–68.

Stevens, G. (1985). Nativity, intermarriage, and mother tongue shift. American Sociological Review, 50(1), 74–83.

Stevens, G. (1992). The social and demographic context of language use in the United States. American Sociological Review, 57, 171–185.

Stoker, L. (1998). Understanding Whites’ resistance to affirmative action: The role of principled commitments and racial prejudice. In J. Hurwitz & M. Peffley (Eds.), Perception and prejudice. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sullivan, J. L., Piereson, J., & Marcus, G. E. (1979). An alternative conceptualization of political tolerance: Illusory increases 1950s–1970s. American Political Science Review, 73(3), 781–794.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Re-discovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Weeks, M. F., & Moore, R. P. (1981). Ethnicity-of-interviewer effects on ethnic respondents. Public Opinion Quarterly, 45, 245–249.

Welch, S., Comer, J., & Steinman, M. (1973). Interviewing in a Mexican-American community: An investigation of some potential sources of response bias. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37, 115–126.

Acknowledgments

Author order is alphabetical. The authors thank Mike Alvarez, Darren Davis, Zoltan Hajnal, Cindy Kam, Paula McClain, Natalie Masuoka, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Ricardo Ramírez, and Lynn Sanders for valuable discussion and comments on this project. The authors are also grateful to the Editors and three anonymous referees for constructive advice on this article.

Ethical standards

This study complies with relevant U.S. laws.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, T., Pérez, E.O. The Persistent Connection Between Language-of-Interview and Latino Political Opinion. Polit Behav 36, 401–425 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9229-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9229-1