Abstract

Objectives

The relatively weak quasi-experimental evaluation design of the original Boston Operation Ceasefire left some uncertainty about the size of the program’s effect on Boston gang violence in the 1990s and did not provide any direct evidence that Boston gangs subjected to the Ceasefire intervention actually changed their offending behaviors. Given the policy influence of the Boston Ceasefire experience, a closer examination of the intervention’s direct effects on street gang violence is needed.

Methods

A more rigorous quasi-experimental evaluation of a reconstituted Boston Ceasefire program used propensity score matching techniques to develop matched treatment gangs and comparison gangs. Growth-curve regression models were then used to estimate the impact of Ceasefire on gun violence trends for the treatment gangs relative to comparisons gangs.

Results

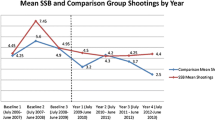

This quasi-experimental evaluation revealed that total shootings involving Boston gangs subjected to the Operation Ceasefire treatment were reduced by a statistically-significant 31 % when compared to total shootings involving matched comparison Boston gangs. Supplementary analyses found that the timing of gun violence reductions for treatment gangs followed the application of the Ceasefire treatment.

Conclusions

This evaluation provides some much needed evidence on street gang behavioral change that was lacking in the original Ceasefire evaluation. A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that jurisdictions should adopt focused deterrence strategies to control street gang violence problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Wright et al. (2004, p. 184) offer a clever metaphor of this perspective: “A restaurant owner can sell more prime rib by lowering its price, but not to vegetarian patrons. The price of prime rib here represents the situational inducement toward ordering meat, but vegetarianism represents a predisposition away from it, and thus the effect of meat pricing significantly varies by level of meat eating.”

See Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 265, Section 15A.

We used data from a recent social network analysis of the rivalries and alliances among Boston gangs to identify the untreated gangs that were socially connected to the N = 19 Ceasefire gangs. Rivalries and alliances between gangs were determined through focus groups with police officers, probation officers, and streetworkers (city-employed gang outreach workers) based on their working knowledge of past and ongoing gang violence. Some gangs connected in rivalries and alliances to Ceasefire gangs also directly received treatment. For instance, the Lucerne Street Doggz had rivalries with eight other gangs and alliances with four other gangs. During the study period, three of their rivals (Castlegate, Morse, and Norfolk) and three of their allies (Favre, Kaos, and Orchard Park) also experienced Ceasefire interventions. N = 22 untreated gangs directly connected to Ceasefire gangs via rivalries or alliances were excluded from consideration for inclusion in our quasi-experimental design. The exercise resulted N = 82 gangs as possible comparison groups (123 total gangs—19 treated gangs—22 untreated gangs that were socially connected to treated gangs = 82 possible comparison gangs).

Gang membership size was calculated from the roster of members of each gang in the BPD BRIC’s gang intelligence database.

We used ArcGIS 10.0 mapping software to map the turf of Boston gangs as polygons that occupied a circumscribed amount of space. We created a matrix of turf adjacency where a tie occurs if any side of a gang polygon touches at least one side of another gang polygon.

Longevity was determined by comparing the roster of N = 123 gangs with at least one shooting during the 2006–2010 study time period to the roster of active Boston gangs in 1995 identified by Kennedy et al. (1997).

The concentrated disadvantage index is a standardized index composed of the percentage of residents who are black, the percentage of residents receiving public assistance, the percentage of families living below the poverty line, the percentage of female-headed households with children under the age of 18, and the percentage of unemployed residents (as measured by the percentage of men over the age 16 who did not work in the previous year) (see Morenoff et al. 2001; Sampson et al. 1997). Because of the high correlation of these variables, we conducted principal components factor analysis, which revealed that variables load on a single factor (which was retained as a standardized index variable). For example, a Boston block group featuring a disadvantage index score of 1.5 would be 1.5 SD more disadvantaged than the mean Boston block group. As such, the disadvantage index is adjusted specifically for the city of Boston using 2000 Census variables, even while the components used to construct the index remain constant across much neighborhood research and remain robust predictors of crime across a variety of city types and spatial aggregations. For those gangs whose turf spanned more than one census block group, we used a spatially-weighted mean of the connected block groups to calculate the disadvantaged index for the neighborhood surrounding each gang’s turf.

For balancing properties to be satisfied in the propensity score matching analysis, certain pre-treatment characteristics needed to be entered as dummy variables into the Stata 12.0 PSMATCH2 routine. The total number of shootings in 2006 and the number of members of each gang were entered as interval-level measures. Adjacent gang turf was coded “0” for gangs that did not have turf adjacent to another gang’s turf and “1” for gangs that did have turf adjacent to another gang’s turf. Longevity was coded “0” for gangs that did not exist in 1995 and “1” for gangs that did exist in 1995. The number of rivalries was coded as “0” for gangs that had 2 or fewer rivalries and “1” for gangs that had 3 or more rivalries. The number of alliances was coded as “0” for gangs that had no alliances and “1” for gangs that had alliances with at least one other gang. Housing project gang was coded as “0” for gangs not located in a housing project and “1” for gangs were located in a housing project. The concentration of disadvantage in the surrounding Census block group(s) was coded as “0” for gang turf located in block groups below the 75th percentile and “1” for gang turf located in block groups at the 75th percentile or greater. The number of gang arrests in 2006 was coded as “0” for gangs with 14 or fewer arrests in 2006 and “1” for gangs with 15 or more arrests in 2006.

The quarterly total gang-involved shootings for the N = 53 treatment and comparison gangs used in these analyses were distributed as overdispersed count data. The distribution had a mean = 1.39, standard deviation = 1.89, and variance = 3.57. One sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov nonparametric tests rejected the null hypotheses that the observed distribution was not different from a normal distribution (p < 0.0001) and not different from a Poisson distribution (p < 0.0001).

Quarter 1 served as the reference category for this polychotomous dummy variable. Quarter 1 represented whether the outcome included the sum of January, February, and March shootings (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Quarter 2 represented whether the outcome included the sum of April, May, and June shootings (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Quarter 3 represented whether the outcome included the sum of July, August, and September shootings (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Quarter 4 represented whether the outcome included the sum of October, November, and December shootings (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Since the selection of a matching algorithm and its particular specification can be a subjective process (Apel and Sweeten 2010), we conducted a supplementary analysis to ensure that any program impacts were robust across a variety of matching algorithms and caliper/bandwidth selections. This exercise was not intended to be an exhaustive examination of all possible propensity score methods. As such, we included a representative selection of approaches: radius matching (calipers = 0.1, 0.01, 0.001), Gaussian kernel matching (bandwidth = 0.1, 0.01, 0.001), Epanechnikov kernel matching (bandwidth = 0.1, 0.01, 0.001), stratification matching (10 strata), and simple nearest neighbor matching. While the estimates differed somewhat across the varying propensity score matching methods, the Ceasefire treatment effect remained robust. The Ceasefire impact estimates ranged from a statistically significant 28 % reduction (p < 0.05) to a statistically significant 35 % reduction (p < 0.05).

A value of Γ = 1.45 for total gang shootings indicates that the confidence interval for the Ceasefire treatment effect would include zero if an unobserved variable caused the chance of treatment assignment to differ between treatment and control groups by 1.45 and if this variable’s effect on total shootings was so strong as to almost perfectly determine whether total shootings would be bigger for the treatment or the control gang in each pair of matched gangs in the data (see DiPrete and Gangl 2004).

Similar conclusions can be drawn by comparing the Rosenbaum bounds results to the ATT models for 2010 suspect shootings (ATT = −3.54, SE = 1.73, p < 0.05) and 2010 victim shootings (ATT = −2.11, SE = 1.24, p < 0.10). For all three ATT models (radius matching, caliper = 0.01), bootstrapped standard errors with 100 replications are provided.

We excluded Quarter 1 and Quarter 20 to ensure that our quarterly impact estimates were based on at least two quarters (6 months) of shooting data for each Ceasefire gang.

Using the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale (Sherman et al. 1997) as a standard, the original Ceasefire impact evaluation would be considered a “Level 3” evaluation and also regarded as the minimum design that is adequate for drawing conclusions about program effectiveness. This design rules out many threats to internal validity such as history, maturation/trends, instrumentation, testing, and mortality. However, as Farrington et al. (2002) observe, the main problems of Level 3 evaluations center on selection effects and regression to the mean due to the non-equivalence of treatment and control conditions. This evaluation of Ceasefire would be considered a “Level 4” evaluation as it measures outcomes before and after the program in multiple treatment and control condition units. These types of designs have better statistical control of extraneous influences on the outcome and, relative to lower level evaluations, deals with selection and regression threats more adequately.

References

Apel RJ, Nagin D (2011) General deterrence: a review of recent evidence. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J (eds) Crime and public policy. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 411–436

Apel RJ, Sweeten G (2010) Propensity score matching in criminology and criminal justice. In: Piquero A, Weisburd DL (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology. Springer, New York, pp 543–562

Austin P, Grootendorst P, Anderson G (2007) A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med 26:734–753

Berk R (2005) Knowing when to fold ‘em: an essay on evaluating the impact of Ceasefire, Compstat, and Exile. Criminol Public Policy 4:451–466

Black D (1970) The production of crime rates. Am Sociol Rev 35:733–748

Blalock H (1979) Social statistics, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Blumstein A (1995) Youth violence, guns, and the illicit-drug industry. J Crim Law Criminol 86:10–36

Blumstein A, Cohen J, Nagin D (eds) (1978) Deterrence and incapacitation: estimating the effects of criminal sanctions on crime rates. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC

Braga AA (2012) Getting deterrence right? Evaluation evidence and complementary crime control mechanisms. Criminol Public Policy 11:201–210

Braga AA, Weisburd DL (2012) The effects of focused deterrence strategies on crime: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. J Res Crime Delinq 49:323–358

Braga AA, Winship C (2006) Partnership, accountability, and innovation: clarifying Boston’s experience with pulling levers. In: Weisburd DL, Braga AA (eds) Police innovation: contrasting perspectives. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 171–190

Braga AA, Kennedy DM, Waring E, Piehl AM (2001) Problem-oriented policing, deterrence, and youth violence: an evaluation of Boston’s Operation Ceasefire. J Res Crime Delinq 38:195–225

Braga AA, Hureau DM, Winship C (2008a) Losing faith? Police, black churches, and the resurgence of youth violence in Boston. Ohio State J Crim Law 6:141–172

Braga AA, Pierce G, McDevitt J, Bond BJ, Cronin S (2008b) The strategic prevention of gun violence among gang-involved offenders. Justice Q 25:132–162

Butterfield F (1996) In Boston, nothing is something. The New York Times, November 21: A20

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S (2005) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching (discussion paper 1588). Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn

Campbell DT, Boruch RF (1975) Making the case for randomized assignment to treatment by considering the alternatives. In: Bennett C, Lumsdaine A (eds) Evaluation and experiments: some critical issues in assessing social programs. Academic Press, New York, pp 195–296

Cohen J, Ludwig J (2003) Policing crime guns. In: Ludwig J, Cook PJ (eds) Evaluating gun policy: effects on crime and violence. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 217–239

Cook PJ (1980) Research in criminal deterrence: laying the groundwork for the second decade. In: Morris N, Tonry M (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 2. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 211–268

Cook P, Laub J (2002) After the epidemic: recent trends in youth violence in the United States. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 29. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1–38

Cook PJ, Ludwig J (2006) Aiming for evidence-based gun policy. J Policy Anal Manage 48:691–735

Corsaro N, McGarrell EF (2009) Testing a promising homicide reduction strategy: reassessing the impact of the Indianapolis “pulling levers” intervention. J Exp Criminol 5:63–82

Corsaro N, Hunt ED, Hipple NK, McGarrell EF (2012) The impact of drug market pulling levers policing on neighborhood violence: an evaluation of the High Point drug market intervention. Criminol Public Policy 11:167–200

Dalton E (2002) Targeted crime reduction efforts in ten communities: lessons for the project safe neighborhoods initiative. US Attorney’s Bull 50:16–25

Decker S (1996) Collective and normative features of gang violence. Justice Q 13:243–264

Decker S, Katz C, Webb V (2008) Understanding the black box of gang organization: implications for involvement in violent crime, drug sales, and violent victimization. Crime Delinq 54:153–172

Dehejia RH, Wahba S (2002) Propensity score matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat 84:151–161

DiPrete T, Gangl M (2004) Assessing bias in the estimation of causal effects: Rosenbaum bounds on matching estimators and instrumental variables estimation with imperfect instruments. Sociol Methodol 34:271–310

Durlauf S, Nagin D (2011) Imprisonment and crime: can both be reduced? Criminol Public Policy 10:13–54

Ellement JR (2007) 25 alleged Boston gang members charged with gun, drug offenses. The Boston Globe, May 24, p A1

Engel RS, Skubak Tillyer M, Corsaro N (2011) Reducing gang violence using focused deterrence: evaluating the cincinnati initiative to reduce violence (CIRV). Justice Q. doi:10.1080/07418825.2011.619559

Fagan J (2002) Policing guns and youth violence. Future Child 12:133–151

Farrington D, Gottfredson D, Sherman L, Welsh B (2002) The Maryland scientific methods scale. In: Sherman L, Farrington D, Welsh B, MacKenzie D (eds) Evidence-based crime prevention. Routledge, London, pp 13–21

Gelman A (2005) Analysis of variance: why it is more important than ever. Ann Stat 33:1–53

Gibbs JP (1975) Crime, punishment, and deterrence. Elsevier, New York

Heckman J, Ichimura H, Todd P (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev Econ Stud 64:605–654

Heckman J, LaLonde R, Smith J (1999) The economics and econometrics of active labor market programs. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1865–2097

Horney J, Marshall IH (1992) Risk perceptions among serious offenders: the role of crime and punishment. Criminology 30:575–594

Hughes L, Short J (2005) Disputes involving gang members: micro-social contexts. Criminology 43:43–76

Imbens GW (2004) Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under exogeneity: a review. Rev Econ Stat 86:4–29

Imbens GW, Wooldredge J (2009) Some recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit 47:5–86

Kennedy DM (1997) Pulling levers: chronic offenders, high-crime settings, and a theory of prevention. Valparaiso Univ Law Rev 31:449–484

Kennedy DM (2011) Don’t shoot. Bloomsbury, New York

Kennedy DM, Piehl AM, Braga AA (1996) Youth violence in Boston: gun markets, serious youth offenders, and a use-reduction strategy. Law Contemp Probl 59:147–196

Kennedy DM, Braga AA, Piehl AM (1997) The (un)known universe: mapping gangs and gang violence in Boston. In: Weisburd D, McEwen JT (eds) Crime mapping and crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 219–262

Klein M (1993) Attempting gang control by suppression: the misuse of deterrence principles. Stud Crime Crime Prev 2:88–111

Klofas J, Hipple NK (2006) Crime incident reviews. Project safe neighborhoods: strategic interventions case study 3. US Department of Justice, Washington, DC

Leuven E, Sianesi B (2003) PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Available online: http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html

Levitt S, Venkatesh S (2000) An economic analysis of a drug-selling gang’s finances. Q J Econ 115:755–789

Lipsey M, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Applied social research methods series, vol 49. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Long JS, Freese J (2006) Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. StataCorp, LP, College Station

Loughran T, Paternoster R, Piquero A, Pogarsky G (2011a) On ambiguity in perceptions of risk: implications for criminal decision making and deterrence. Criminology 49:1029–1061

Loughran T, Pogarsky G, Piquero A, Paternoster R (2011b) Re-examining the functional form of the certainty effect in deterrence theory. Justice Q 29(5):712–741

Ludwig J (2005) Better gun enforcement, less crime. Criminol Public Policy 4:677–716

McGarrell EF, Chermak S, Weiss A, Wilson J (2001) Reducing firearms violence through directed police patrol. Criminol Public Policy 1:119–148

McGarrell EF, Chermak S, Wilson J, Corsaro N (2006) Reducing homicide through a ‘lever-pulling’ strategy. Justice Q 23:214–229

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 39:517–559

Morgan SL, Winship C (2007) Counterfactuals and causal inference: methods and principals for social research. Cambridge University Press, New York

Nagin D (1998) Criminal deterrence research at the outset of the twenty-first century. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 23. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1–42

Papachristos A (2009) Murder by structure: dominance relations and the social structure of gang homicide. Am J Soc 115:74–128

Papachristos A, Kirk D (2006) Neighborhood effects and street gang behavior. In: Short J (ed) Studying youth gangs. Alta Mira, Landham, pp 63–84

Papachristos A, Meares T, Fagan J (2007) Attention felons: evaluating project safe neighborhoods in Chicago. J Emp Legal Stud 4:223–272

Paternoster R (1987) The deterrent effect of the perceived certainty and severity of punishment: a review of the evidence and issues. Justice Q 4:173–217

Piehl AM, Cooper SJ, Braga AA, Kennedy DM (2003) Testing for structural breaks in the evaluation of programs. Rev Econ Stat 85:550–558

Rosenbaum P (2002) Observational studies, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–55

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1985) Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 39:33–38

Rosenfeld R, Bray TM, Egley A (1999) Facilitating violence: a comparison of gang-motivated, gang-affiliated, and nongang youth homicides. J Quant Criminol 15:495–516

Rosenfeld R, Fornango R, Baumer E (2005) Did Ceasefire, Compstat, and Exile reduce homicide? Criminol Public Policy 4:419–450

Rossi PH, Lipsey M, Freeman H (2006) Evaluation: a systematic approach, 7th edn. Sage, Newbury Park

Rubin DB (1990) Formal modes of statistical inferences for causal effects. J Stat Plan Inference 25:279–292

Sampson RJ, Wilson WJ (1995) Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality. In: Hagan J, Peterson R (eds) Crime and inequality. Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp 37–56

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Schneider VW, Wiersema B (1990) Limits and use of uniform crime reports. In: MacKenzie DL, Baunach PJ, Roberg RR (eds) Measuring crime. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 21–48

Seabrook J (2009) Don’t shoot: a radical approach to the problem of gang violence. The New Yorker, June 22, pp 32–39

Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D (2002) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Sherman LW, Rogan D (1995) Effects of gun seizures on gun violence: ‘hot spots’ patrol in Kansas City. Justice Q 12:755–782

Sherman LW, Gottfredson D, MacKenzie DL, Eck JE, Reuter P, Bushway S (1997) Preventing crime: what works, what doesn’t, what’s promising. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

Singer JD, Willet JB (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, New York

Smith C (2012) The influence of gentrification on gang homicides in Chicago neighborhoods, 1994 to 2005. Crime Delinq. doi:10.1177/0011128712446052

Smith J, Todd P (2005) Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? J Econom 125:303–353

Tita G, Greenbaum R (2009) Crime, neighborhoods, and units of analysis: putting space in its place. In: Weisburd D, Bernasco W, Bruinsma G (eds) Putting crime in its place. Springer, New York, pp 145–170

Tita G, Radil S (2011) Spatializing the social networks of gangs to explore patterns of violence. J Quant Criminol 27:521–545

Tita G, Riley J, Ridgeway G, Grammich C, Abrahamse A, Greenwood P (2004) Reducing gun violence: results from an intervention in East Los Angeles. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica

Travis J (1998) Crime, justice, and public policy. Plenary presentation to the American Society of Criminology, (http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/speeches/asc.htm), November 1, Washington, DC

Weisburd D, Lum C, Petrosino A (2001) Does research design affect study outcomes in criminal justice? Annals 578:50–70

Wellford CF, Pepper JV, Petrie CV (eds) (2005) Firearms and violence: a critical review. Committee to improve research information and data on firearms. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Welsh BC, Peel ME, Farrington DP, Elffers H, Braga AA (2011) Research design influence on study outcomes in crime and justice: a partial replication with public area surveillance. J Exp Criminol 7:183–198

Wilkinson L, Task Force on Statistical Inference (1999) Statistical methods in psychology journals: guidelines and expectations. Am Psychol 54:594–604

Witkin G (1997) Sixteen silver bullets: smart ideas to fix the world. US News and World Report, December 29, p 67

Wright B, Caspi A, Moffitt T, Paternoster R (2004) Does the perceived risk of punishment deter criminally prone individuals? Rational choice, self-control, and crime. J Res Crime Delinq 41:180–213

Zimring F (1968) Is gun control likely to reduce violent killings? Univ Chic Law Rev 35:21–37

Zimring F (1972) The medium is the message: Firearm caliber as a determinant of death from assault. J Legal Stud 1:97–124

Zimring F, Hawkins G (1973) Deterrence: the legal threat in crime control. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braga, A.A., Hureau, D.M. & Papachristos, A.V. Deterring Gang-Involved Gun Violence: Measuring the Impact of Boston’s Operation Ceasefire on Street Gang Behavior. J Quant Criminol 30, 113–139 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9198-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9198-x