Abstract

Research is needed to understand the extent to which environmental factors moderate links between genetic risk and the development of smoking behaviors. The Vietnam-era draft lottery offers a unique opportunity to investigate whether genetic susceptibility to smoking is influenced by risky environments in young adulthood. Access to free or reduced-price cigarettes coupled with the stress of military life meant conscripts were exposed to a large, exogenous shock to smoking behavior at a young age. Using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we interact a genetic risk score for smoking initiation with instrumented veteran status in an instrumental variables (IV) framework to test for genetic moderation (i.e. heterogeneous treatment effects) of veteran status on smoking behavior and smoking-related morbidities. We find evidence that veterans with a high genetic predisposition for smoking were more likely to have been smokers, smoke heavily, and are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with cancer or hypertension at older ages. Smoking behavior was significantly attenuated for high-risk veterans who attended college after the war, indicating post-service schooling gains from veterans’ use of the GI Bill may have reduced tobacco consumption in adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (Grant Number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

The RAND HRS Data file (Version N, 2014) is an easy to use longitudinal data set based on the HRS data. It was developed at RAND with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration, Santa Monica.

See “Genetic risk score” section for QC specifics.

In 1994 and 1996, the smoking questions were fielded to current smokers only. However, since questions about former smoking behavior were asked in 1992, and a new cohort was not added until 1998, data on past smoking behavior is available for the majority of participants.

In general, self-reports of smoking behavior have been shown to be a reliable measure over time despite mounting social stigma (Hatziandreu et al. 1989) and findings from biochemical validation studies suggest self-reported usage is a valid estimate of smoking status in the population (Fortmann et al. 1984; Patrick et al. 1994).

We also explored outcomes related to lung disease and lung function but failed to find any significant effects. Results are available from the authors upon request.

\(Mean \; arterial \; pressure \; \left( {MAP} \right) \cong \frac{2}{3} \times DBP + \frac{1}{3} \times SBP.\)

The results of the Vietnam draft lottery are available at: http://www.sss.gov/lotter1.htm.

Specifically, we regress veteran status on draft eligibility and a constant with controls for month of birth. Men born between 1948 and 1952 were 15.7 % points more likely to serve, while men born between 1950 and 1952 were 15.3 % points more likely to serve. Results are available from the authors upon request.

Genotyping was performed on the HRS sample using the Illumina Human Omni-2.5 Quad beadchip (HumanOmni2.5-4v1 array). The median call-rate for the 2006–2008 samples is 99.7 %.

Clumping takes place in two steps. The first pass is done in fairly narrow windows (250 kb) for all SNPs (the p value significance thresholds for both index and secondary SNPs is set to 1) with a liberal LD threshold (R2 = 0.5). In a second pass, SNPs remaining after the first prune are again pruned in broader windows (5000 kb) but with a more conservative LD threshold (R2 = 0.2).

GxE interaction models with the CPD GRS are available from the authors upon request.

The first condition is easy to verify, and standard first stage statistics (partial R2 and F-statistic) for the significance of the instruments in the HRS sample show draft eligibility and its interaction with the GRS are robust predictors of veteran status and its interaction with the GRS (tables are available upon request). The exclusion restriction, or second condition, cannot directly be tested. In this study, a violation of the exclusion restriction could occur if the stress of having a low draft number triggered smoking behavior. Heckman (1997) shows the IV estimator is not consistent if heterogeneous behavioral responses to the treatment—or military service in this case—are correlated with the instrument (i.e. draft eligibility). However, past research has provided convincing counterfactuals that suggest the exclusion restriction holds. For example, Angrist (1990) found no significant relationship between earnings and draft eligibility status for men born in 1953 (where draft eligibility was defined using the 1952 lottery cutoff of 95). Since the 1953 cohort was assigned RSNs but never called to service, if the draft affected outcomes directly, we would expect outcomes to vary by draft eligibility for this cohort.

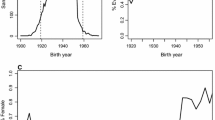

A mechanical failure in the implementation of the first round of the lottery (balls with the days of the year were not mixed sufficiently after having been dumped in a month at a time) resulted in a disproportionately high probability of being drafted for those born in the last few months of the year (Fienberg 1971). This could bias estimates if those born later in the year differ in important ways from those born at other times during the year. For example, studies have shown health varies with season of birth.

In a typical linear regression model with an interaction term, the interaction term and each of the corresponding main effects are included as separate terms (e.g. “draft”, “GRS x draft” and “GRS”). Here, because we are using a 2SLS approach, and the “GRS” term is highly correlated with “GRS x draft”, we model the main effect of the GRS as “nodraft x GRS” to strengthen the correlation between the “GRS x veteran” and the “GRS × draft” terms in the first stage. Using the GxE interaction term for draft ineligible non-veterans instead of the main effect of the GRS does not change the meaning of this term, which can still be interpreted as the marginal effect or slope for men who were not drafted and who did not serve. However, it does change the interpretation of \(\updelta_{2}\), which now represents the marginal effect for draft eligible veterans instead of the difference between the marginal effects for draft eligible veterans and draft ineligible non-veterans.

The IV estimates of effects of military service using the draft lottery capture the effect of military service on “compliers”, or men who served because they were draft eligible but who would not otherwise have served. It is not, therefore, an estimate of the effect of military service on men who volunteered. See Angrist and Pischke (2008) for a more detailed discussion of the interpretation of the LATE for the Vietnam-era draft.

Post hoc power analysis was conducted for the GxE coefficients using the software package G*Power (Faul et al. 2009). The sample size of 631 was used for statistical power analysis on a multivariate linear regression equation with 83 predictors at the conventional, two-tailed 0.05 significance level (\(\alpha = 0.05)\).

The partial R2 or Cohen’s effect size for the GxE coefficient was estimated from an OLS regression of Eq. 4. To minimize any potential bias in the estimation of the effect sizes due to the endogeneity of self-reported veteran status, we model the GxE interaction terms in the OLS model using draft eligibility status instead of self-reported veteran status.

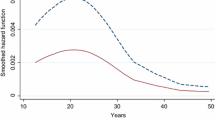

Specifically, we estimate the total difference between veterans and non-veterans, or the total treatment effect, by adding the marginal treatment effects for veterans (“Veteran” + “GRS x Veteran”) and subtracting them from the marginal treatment effect for draft ineligible non-veterans (“GRS × Non-Veteran”). To ensure the accuracy of the standard errors, this is done using a post-estimation linear combination.

We note that due to low sample sizes at higher values of the GRS, IV estimates three or more standard deviations away from the mean may not accurately predict total treatment effects.

The exogenous downstream effect of educational attainment might be compromised if the high correlation between draft eligibility and schooling is a reflection of draft avoidance behavior rather than military service—i.e. if it is a capturing the effect of men with low draft lottery numbers who “beat the draft” by obtaining educational deferments. Angrist and Chen (2011) find small but statistically significant positive effects of service on educational attainment for white men born between 1948 and 1952. Weighing this against the sharp decline in educational deferments during the draft lottery period, they argue there is little evidence to support the claim that increases in schooling among draft eligible men are due to draft avoidance behavior.

References

Angrist JD (1990) Lifetime earnings and the Vietnam-era draft lottery: evidence from social security administrative records. Am Econ Rev 80:313–336

Angrist JD, Chen SH (2011) Schooling and the Vietnam-era GI bill: evidence from the draft lottery. Am Econ J 3(2):96–118

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (2001) Instrumental variables and the search for identification: from supply and demand to natural experiments. J Econ Perspect 15(4):69–85

Angrist JD, Pischke JS (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Angrist JD, Chen SH, Frandsen BR (2010) Did Vietnam veterans get sicker in the 1990s? The complicated effects of military service on self-reported health. J Public Econ 94(11):824–837

Angrist JD, Chen SH, Song J (2011) Long-term consequences of Vietnam-era conscription: new estimates using Social Security data. Am Econ Rev 101(3):334–338

Batty GD, Deary IJ, Gottfredson LS (2007) Premorbid (early life) IQ and later mortality risk: systematic review. Ann Epidemiol 17(4):278–288

Bedard K, Deschênes O (2006) The long-term impact of military service on health: Evidence from World War II and Korean War veterans. Am Econ Rev 96:176–194

Belsky DW, Moffitt TE, Baker TB, Biddle AK, Evans JP, Harrington HL, Williams B (2013) Polygenic risk and the developmental progression to heavy, persistent smoking and nicotine dependence: evidence from a 4-decade longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry 70(5):534–542

Benetos A, Safar M, Rudnichi A, Smulyan H, Richard JL, Ducimetière P, Guize L (1997) Pulse pressure a predictor of long-term cardiovascular mortality in a French male population. Hypertension 30(6):1410–1415

Boardman JD, Saint O, Jarron M, Haberstick BC, Timberlake DS, Hewitt JK (2008) Do schools moderate the genetic determinants of smoking? Behav Genet 38(3):234–246

Bound J, Turner S (2002) Going to war and going to college: did World War II and the GI bill increase educational attainment for returning veterans? J Labor Econ 20(4):784–815

Card, D., & Lemieux, T. (2001). Going to college to avoid the draft: The unintended legacy of the Vietnam War. American Economic Review, 97-102

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (1994) Surveillance for selected tobacco-use behaviors–United States, 1900–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 43(3):1–43

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2003) Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults and changes in prevalence of current and some day smoking—United States, 1996–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 52(14):303

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2008) Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57(45):1226

Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier LCAM, Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M,. Lee J.J. (2015). Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience, 4

Conley D (2009) The promise and challenges of incorporating genetic data into longitudinal social science surveys and research. Biodemogr Soc Biol 55(2):238–251

Conley D, Heerwig JA (2011) The war at home: effects of Vietnam-era military service on postwar household stability. Am Econ Rev 101(3):350–354

Conley D, Heerwig JA (2012) The long-term effects of military conscription on mortality: estimates from the Vietnam-era draft lottery. Demography 49(3):841–855

Daw J, Shanahan M, Harris KM, Smolen A, Haberstick B, Boardman JD (2013) Genetic sensitivity to peer behaviors 5HTTLPR, smoking, and alcohol consumption. J Health Soc Behav 54(1):92–108

De Walque D (2007) Does education affect smoking behaviors?: evidence using the Vietnam draft as an instrument for college education. Journal of Health Economics 26(5):877–895

De Walque D (2010) Education, information, and smoking decisions evidence from smoking histories in the United States, 1940–2000. J Hum Resour 45(3):682–717

Dobkin C, Shabani R (2009) The health effects of military service: evidence from the Vietnam draft. Econ Inq 47(1):69–80

Eisenberg D, Rowe B (2009) The effect of smoking in young adulthood on smoking later in life: evidence based on the Vietnam era draft lottery. In: Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 12(2), Health Policy and Planning, Beijing

Farrell P, Fuchs VR (1982) Schooling and health: the cigarette connection. J Health Econ 1(3):217–230

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41:1149–1160

Fienberg SE (1971) Randomization and social affairs: the 1970 draft lottery. Science 171(3968):255–261

Fletcher JM, Conley D (2013) The challenge of causal inference in gene–environment interaction research: leveraging research designs from the social sciences. Am J Public Health 103(S1):S42–S45

Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Vranizan K, Haskell WL, Solomon DS, Farquhar JW (1984) Indirect measures of cigarette use: expired-air carbon monoxide versus plasma thiocyanate. Prev Med 13(1):127–135

Fuchs, V. R. (1982). Time preference and health: An exploratory study. Economic Aspects of Health, 93

Furberg H, Kim Y, Dackor J, Boerwinkle E, Franceschini N, Ardissino D, Merlini PA (2010) Genome-wide meta-analyses identify multiple loci associated with smoking behavior. Nat Genet 42(5):441–447

Gimbel C, Booth A (1996) Who fought in Vietnam? Soc Forces 74(4):1137–1157

Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J (1990) Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA 264(12):1546–1549

Grimard F, Parent D (2007) Education and smoking: were Vietnam war draft avoiders also more likely to avoid smoking? J Health Econ 26(5):896–926

Grossman M (1972) On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Polit Econ 80(2):223–255

Grossman M (2006) Education and nonmarket outcomes. Handb Econ Educ 1:577–633

Hatziandreu EJ, Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Grise V, Novotny TE, Davis RM (1989) The reliability of self-reported cigarette consumption in the United States. Am J Public Health 79(8):1020–1023

Health and Retirement Study (1992–2010 Core Files) public use dataset and (1992–2010 Respondent Date of Birth Files) restricted use dataset (2014) Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740), Ann Arbor

Hearst N, Newman TB, Hulley SB (1986) Delayed effects of the military draft on mortality: a randomized natural experiment. N Eng J Med 314(10):620

Heckman J (1997) Instrumental variables: a study of implicit behavioral assumptions used in making program evaluations. J Hum Resour 32:41–462

Heerwig JA, Conley D (2013) The causal effects of Vietnam-era military service on post-war family dynamics. Soc Sci Res 42(2):299–310

Helyer AJ, Brehm WT, Perino L (1998) Economic consequences of tobacco use for the Department of Defense, 1995. Mil Med 163(4):217–221

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE (2005) Monitoring the future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2004, volume II, College students and adults ages 19–45, 2004, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Kandel DB, Logan JA (1984) Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: periods of risk for initiation, continued use, and discontinuation. Am J Public Health 74(7):660–666

Kendler KS, Gardner C, Jacobson KC, Neale MC, Prescott CA (2005) Genetic and environmental influences on illicit drug use and tobacco use across birth cohorts. Psychol Med 35(09):1349–1356

Le Marchand L, Derby KS, Murphy SE, Hecht SS, Hatsukami D, Carmella SG, Wang H (2008) Smokers with the CHRNA lung cancer–associated variants are exposed to higher levels of nicotine equivalents and a carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamine. Cancer Res 68(22):9137–9140

Liu JZ, Tozzi F, Waterworth DM, Pillai SG, Muglia P, Middleton L, Waeber G (2010) Meta-analysis and imputation refines the association of 15q25 with smoking quantity. Nat Genet 42(5):436–440

Lleras-Muney A (2005) The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States. Rev Econ Stud 72(1):189–221

Maes HH, Woodard CE, Murrelle L, Meyer JM, Silberg JL, Hewitt JK, Carbonneau R (1999) Tobacco, alcohol and drug use in eight-to sixteen-year-old twins: the Virginia Twin study of adolescent behavioral development. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 60(3):293

Merline AC, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD (2004) Substance use among adults 35 years of age: prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. Am J Public Health 94(1):96–102

Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S (1994) The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 84(7):1086–1093

Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D (2006) Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 38(8):904–909

Purcell S, Chang C (2014) PLINK [Computer software]. https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2

Rouse B, Sanderson C, Feldmann J (2002) Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of National Findings, vol I. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, Rockville

Slomkowski C, Rende R, Novak S, Lloyd-Richardson E, Niaura R (2005) Sibling effects on smoking in adolescence: evidence for social influence from a genetically informative design. Addiction 100(4):430–438

Spitz MR, Amos CI, Dong Q, Lin J, Wu X (2008) The CHRNA5-A3 region on chromosome 15q24-25.1 is a risk factor both for nicotine dependence and for lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(21):1552–1556

Stanley M (2003) College education and the midcentury GI Bills. Q J Econ 118(2):671–708

StataCorp (2013) Stata statistical software: release 13. StataCorp LP, College Station

Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, Oskarsson H (2008) A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452(7187):638–642

Thorgeirsson TE, Gudbjartsson DF, Surakka I, Vink JM, Amin N, Geller F, Walter S (2010) Sequence variants at CHRNB3-CHRNA6 and CYP2A6 affect smoking behavior. Nat Genet 42(5):448–453

Timberlake DS, Rhee SH, Haberstick BC, Hopfer C, Ehringer M, Lessem JM, Hewitt JK (2006) The moderating effects of religiosity on the genetic and environmental determinants of smoking initiation. Nicot Tob Res 8(1):123–133

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1989) Reducing the health consequences of smoking: 25 years of progress. A report of the surgeon general. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 89-8411

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1990) A report of the surgeon general: the health benefits of smoking cessation, Washington, DC

U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (2015) Vietnam Veterans. http://www.benefits.va.gov/persona/veteran-vietnam.asp

U.S. Selective Service System (2015) Induction statistics. https://www.sss.gov/induct.htm

Wedge R, Bondurant S (eds) (2009) Combating tobacco use in military and veteran populations. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Winefield HR, Winefield AH, Tiggemann M, Goldney RD (1989) Psychological concomitants of tobacco and alcohol use in young Australian adults. Br J Addict 84(9):1067–1073

Funding

This study was funded by the Russell Sage Foundation (grant number 83-15-29).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Lauren Schmitz and Dalton Conley declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitz, L., Conley, D. The Long-Term Consequences of Vietnam-Era Conscription and Genotype on Smoking Behavior and Health. Behav Genet 46, 43–58 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-015-9739-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-015-9739-1